Corn Earworm on Vegetables

ID

3103-1537 (SPES-624NP)

Introduction

The corn earworm, Helicoverpa zea (Boddie) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), is one of the most damaging pests of agricultural crops in Virginia. It is also known as tomato fruitworm, cotton bollworm, bean podworm, sorghum headworm, and vetchworm. It feeds on a wide variety of fruiting and podding plants, including many vegetables.

Moths deposit eggs on flowering plants, where larvae prefer to feed on reproductive plant structures like flowers or fruit. Herein, we review the general biology and management of this important pest in vegetable crops.

Life Cycle and Description

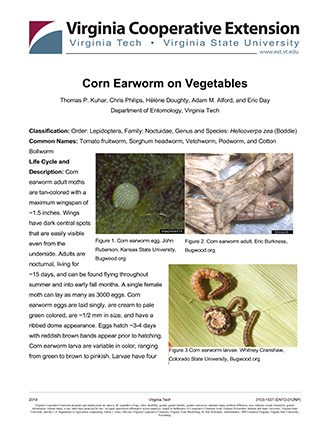

Adult corn earworm (CEW) moths are tan colored with a maximum wingspan of 1.5 inches (Figure 1). Wings have dark central spots that are easily visible even from the underside. Adults are nocturnal, live for about 15 days, and can be found flying from early summer to early fall. A single female moth can lay as many as 3,000 eggs. Eggs are laid singly, are cream to pale green colored, are about 0.5 mm in size, and have a ribbed dome appearance. Eggs hatch in 2-4 days, with reddish brown bands that appear prior to hatching (Bragard et al. 2020).

CEW larvae are variable in color, ranging from yellow, green, brown to pinkish (Figure 2). Larvae have four pairs of abdominal prolegs, a reddish- brown head, and pale lateral lines along the length of the body. Larvae undergo six instars (or molts) in 2- 3 weeks depending on temperature and grow from about 1 mm to almost 2 inches long during their development. Upon completion of development, larvae drop to the ground from the infested crop, where they then burrow about 2-4 inches into the soil to pupate (in summer) or in the fall, to overwinter, then pupate in the spring. CEW pupae are about 0.5-1 inch in length and dark brown.

Host Plants

CEW larvae have a very broad host range and can feed and develop on >300 different host plants, including many vegetable crops. Sweet corn, tomatoes, beans, and pepper are the most attacked vegetables within Virginia. Silking sweet corn is the most attractive host plant to egg-laying females (Olmstead et al. 2016).

Damage to Vegetables

In corn, CEW larvae feed on the tassels, silks, and kernels often near the tip of a corn ear (Figure 3). On fruiting vegetables like tomato, larvae feed on fruit, often damaging more than one fruit per larva (Figure 4). On beans and many other vegetables, larvae feed on flowers and pods.

Monitoring Thresholds

The relative density of CEW moths on a farm can be monitored using pheromone traps. Typical traps include heliothis (soft synthetic mesh), or hartstack (wire mesh) traps baited with a CEW mating pheromone lure. Blacklight traps can also be used for monitoring adults. Moth catch per night is monitored and can be used to guide the number of days needed between insecticide applications. If seven or more moths are caught per night, an insecticide treatment should be considered.

On tomatoes and other vegetables, plants can be visually inspected for eggs and larvae. At least 20 plants should be observed per field for any sign of eggs, which are generally laid on leaves below the highest flower cluster, or actively feeding CEW larvae (Kuhar et al. 2006).

Non-chemical Control Options

In the Mid-Atlantic Region, CEW is typically a late summer pest of vegetables, so spring-planted vegetables often escape significant pest pressure.

Generally, sweet corn, beans, and tomatoes harvested before mid-July escape serious pest damage. A wide range of arthropod natural enemies feed on CEW eggs and larvae and can help suppress pest numbers, but often this pest overwhelms any biological control efforts, especially in sweet corn. (Reay-Jones 2019)

In sweet corn, applying oil (mineral oil or vegetable oil) to the silks during fresh silking period can kill eggs and tiny hatchlings before they make it down the silk and into the ear where they are protected from subsequent insecticide applications. (Ni, Sparks, Reiley, and Li 2011)

Plants treated with kaolin clay (Surround WP) have fewer pests overall, including CEW, which avoid depositing eggs on treated plants.

Chemical Control

Corn earworm populations have developed resistance to Bt Cry proteins (e.g., trade name Dipel, Javelin, Thuricide) (Dively et al. 2021) as well as synthetic pyrethroids (Hopkins and Pietrantonio 2010). Neither of these classes of insecticides are recommended for this pest anymore. More lepidopteran-targeted insecticides such as diamides, spinosyns, and several others provide effective control of this pest (López, Latheef and Hoffman 2014). Many are labeled for use on vegetables.

For sweet corn under moderate to high pest pressure (7+ moths caught per night), apply insecticides at 2- to 3-day intervals during silking. For green beans, treat when pods are 1 inch long (pin stage) and weekly thereafter. For tomato, treat every 5-7 days, beginning at fruit set and continuing as long as needed while fruit are present.

For up-to-date CEW control recommendations on vegetables, refer to the most recent Mid-Atlantic Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations VCE Publ. No. 456-420 (SPES- 103P) https://pubs.ext.vt.edu/456/456-420/456-420.html

References

Bragard, C., K. Dehnen‐Schmutz, F. Di Serio, P. Gonthier, M. Jacques, J. A. Jaques Miret, A. F. Justesen, C. S. Magnusson, P. Milonas, J. A. Navas‐Cortes, S. Parnell, R. Potting, P. L. Reignault, H. Thulke, W. Van der Werf, A. V. Civera, J. Yuen, L. Zappalà, E. Czwienczek, and A. MacLeod. 2020. “Pest Categorisation of Helicoverpa zea.” EFSA Journal 18(7). https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6177

Dively, G. P., P. D. Venugopal, and C. Finkenbinder. 2016. “Field-Evolved Resistance in Corn Earworm to Cry Proteins Expressed by Transgenic Sweet Corn.” PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169115

Dively, G. P., T. P. Kuhar, S. Taylor, H. B. Doughty, K. Holmstrom, D. Gilrein, B. A. Nault, J. Ingerson-Mahar, J. Whalen, D. Reisig, D. L. Frank, S. J. Fleischer, D. Owens, C. Welty, F. Reay-Jones, P. Porter, J. L. Smith, J. Saguez, S. Murray, A. Wallingford, H. Byker, B. Jensen, E. Burkness, W. D. Hutchison, and K. A. Hamby. 2021. “Sweet Corn Sentinel Monitoring for Lepidopteran Field-Evolved Resistance to Bt Toxins.” Journal of Economic Entomology 114(1):307-319. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaa264

Hopkins, B. W. and P. V. Pietrantonio. 2010. “Differential Efficacy of Three Commonly Used Pyrethroids Against Laboratory and Field- Collected Larvae and Adults of Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Significance for Pyrethroid Resistance Management.” Pest Management Science. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.1847

López, J. D., M. A. Latheef, and W. C. Hoffmann. 2014. “Toxicity and Feeding Response of Adult Corn Earworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to an Organic Spinosad Formulation in Sucrose Solution.” Advances in Entomology 2(1). https://doi.org/10.4236/ae.2014.21006

Olmstead, D. L, B. A. Nault, and A. M. Shelton. 2016. “Biology, Ecology, and Evolving Management of Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Sweet Corn in the United States.” Journal of Economic Entomology 109(4):1667- 1676. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tow125

Reay-Jones, F. P. 2019. “Pest Status and Management of Corn Earworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Field Corn in the United States.” Journal of Integrated Pest Management. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmz017

Ni, X., A. N. Sparks, D. G. Riley, and X. Li. 2011. “Impact of Applying Edible Oils to Silk Channels on Ear Pests of Sweet Corn.” J Econ Entomology 104(3). https://doi.org/10.1603/ec10356

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

October 21, 2024