Sustaining America's Aquatic Biodiversity - Crayfish Biodiversity and Conservation

ID

420-524 (CNRE-82P)

Of the approximately 500 crayfishes (sometimes called crawdads or crawfish) found on earth, about 400 crayfish species live in waters in North America, and about 353, nearly 70 percent of the world’s total species, inhabit waters in the United States. Freshwater habitats throughout the United States harbor the richest diversity of these aquatic animals in the world.

The majority of crayfish species live east of the Rocky Mountains and in the Southeastern states. Many live in streams, rivers, and lakes, while others are restricted to springs, swamps, and even un- derground waters (cave crayfish). Native crayfish come in a variety of colors (white, blue, red, brown, gray, yellow), shapes, and sizes (1 to 6 inches in length).

Crayfish serve as important links in the food chain, feeding on living and dead plants, other invertebrates, and fish. They are a primary food for fish (bass), water birds (herons), mammals (raccoons), and others. In fact, over 240 species of wild animals in North America eat crayfish.

Like its saltwater cousin, the lobster, the crayfish is sold as gourmet food. Nearly 80,000 tons of crayfish, with a value of more than $200 million, are farmed in ponds or trapped in wetlands each year. Crayfish also are important indicators of water quality and environmental health, flourishing in clean waters and perishing in polluted waters. Most crayfish live from 2 to 4 years, although some cave crayfish may live over 10 years.

Crayfish are threatened by habitat destruction caused by dams, water pollution, erosion, siltation, in-stream gravel dredging and, particularly, the introduction of nonnative crayfishes and other exotics. About 65 species of crayfish are endangered, threatened, or listed as species of special concern by the states in which they live, and 48 percent of our native crayfish species are in need of protection. These numbers are best estimates only. The exact status of crayfish endangerment or extinction rates in the United States is largely unknown because very few distribution and population surveys have been completed.

Most Americans believe that we should protect our native aquatic animals as a legacy to our children. Citizens can help safeguard life in our waterways. To protect our aquatic biodiversity, they can join conservation groups, adopt a local stream or river, and report all suspected water pollution problems to state natural resource agencies.

What Is a Crayfish?

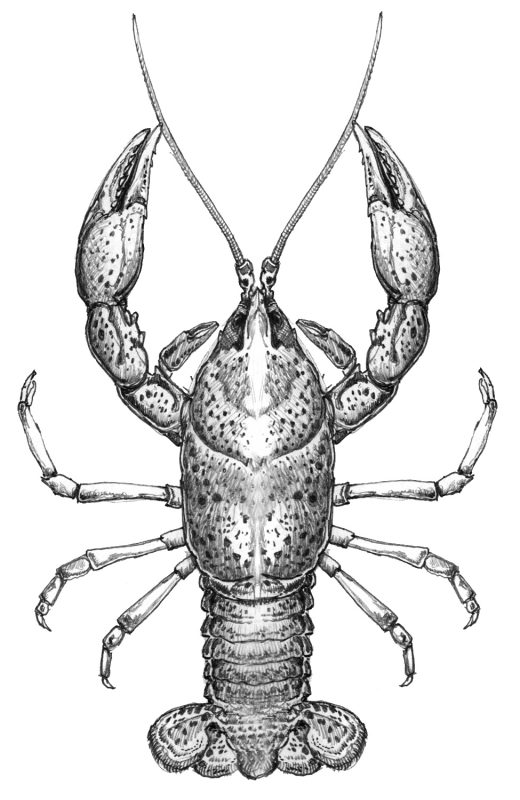

Crayfish are small lobster-like animals that live in freshwater streams, ponds, lakes, swamps, and marshes throughout the world. They are invertebrates (animals without a backbone) that belong to a group called the Arthropoda (joint-footed) animals related to the insects, spiders, scorpions, millipedes, and mites. They belong to the group Crustacea (shell) and the order Decapoda (ten legs).

Some say the name comes from the word “cray” which refers to a hole or burrow. Carapace Others believe it is from a French word meaning “crevice.” Some crayfish dig and live their entire lives in burrows. Native American crayfish are a diverse and interesting group of aquatic animals; they come in a variety of sizes, shapes, colors, and forms.

What do they look like?

Crayfish, as other Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, and shrimp), are heavily armored with a hard exoskeleton or “shell,” that must be shed periodically so that the animal can grow. This exoskeleton serves to protect the crayfish from predators and provides a framework for the body. Despite its hard armored shell, the crayfish is agile and fast, thanks to flexible, jointed segments.

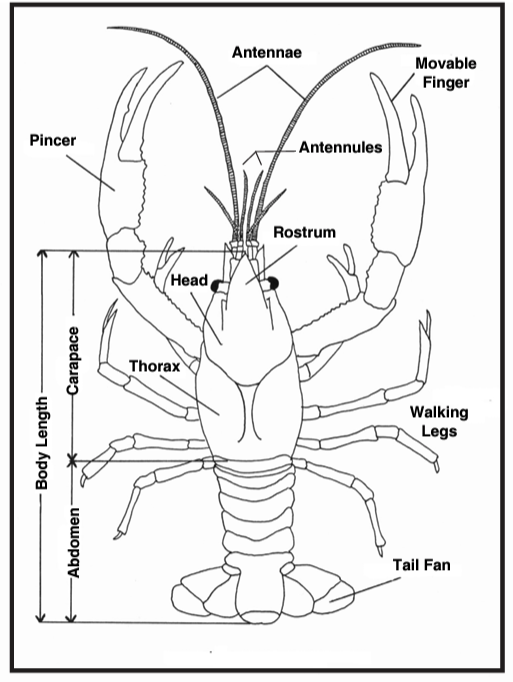

The body of the crayfish consists of two sections:

- the front of the body called the cephalothorax (head and chest) and,

- the abdomen or rear half of the body.

The cephalothorax of the body is entirely covered by the shell (carapace), whereas the back part of the body or abdomen consists of seven jointed segments and a large, fan-like tail.

They have two large, compound eyes consisting of thousands of eyelets (providing a mosaic view like that of insects) supported on stalks.

They use their two kinds of antennae (short, jointed inner antennules and long outer antennae) to taste the water and find food. The inner antennules are used for chemoreception (tasting the water and food). The outer ones are used for the sense of touch. The over-lapping mouth parts and heavy tooth-like mandibles are used to crush and shred food before it is eaten.

Crayfish have ten legs (one pair of large claws and four pairs of slender walking legs). The first pair of legs has the claws (pincers), which are used for defense, mating, burrow building, egg laying in females, and feeding. These strong claws are specialized for capturing, cutting, and crushing food. Their pinch can hurt. When threatened, the crayfish assumes a defensive position with the body lifted and the claws elevated and spread. At this time the crayfish may retreat slowly by walking backwards.

The first two pairs of small walking legs are tipped with small pincers that are used to probe in cracks and holes for food, and are used for eating, walking, and grooming. The last two pair of legs are used for walking and mating. Crayfish can regenerate their limbs if they are broken off, but regenerated legs and claws often are smaller or misshapen when compared to the originals.

The large, fan-shaped tail, flattened from top to bottom, is used for quickly swimming backwards. Large muscles in the abdomen curl the tail fan forward beneath the body propelling the crayfish rapidly backwards. Typically crayfish walk slowly forward on their legs, but if they are startled, crayfish use rapid flips of their tails to quickly swim backwards in a series of jerking movements to escape danger.

Crayfish breathe by internal gills like fish, but many (especially burrowing crayfish) can remain out of water for considerable amounts of time under humid conditions. The plume-like gills are located in gill chambers on each side of the body. Gill flaps attached to the mouthparts help circulate oxygenated water for breathing.

Scientists use the size, shape, color, shell markings, and reproductive organs to identify the many species. Crayfish can vary in color from white to blue to red to green to black or brown. Most crayfish are brown-green in color in order to blend into the stream bottom and hide from predators.

Where do they live?

Crayfish live in a range of habitats including clean, flowing waters (streams, rivers) and standing waters (ponds, lakes, marshes, swamps). They are found in almost any wetland, including drainage ditches; wherever there is water. Some species have adapted to living in ponds, but most live in streams and rivers where water flows provide an abundant oxygen supply for breathing. Crayfish live in a wide range of water temperatures from 55˚F to >80˚F.

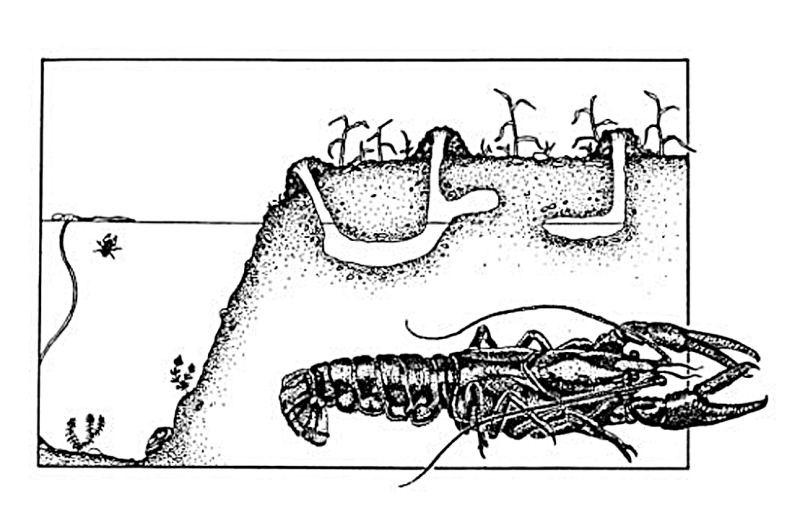

Nearly all crayfish use some type of shelter during part or all of their lives. Many spend most of their lives walking on stream and lake bottoms (largely at night), but quickly burrow under rocks and logs to avoid predators. Some crayfish spend their entire lives underground and only come out to feed and mate.

Burrowing crayfish are rarely seen above ground during the daytime. Burrowing crayfish dig holes in stream banks and in moist soils. Crayfish usually dig tunnels from 1 to 5 feet deep or to the water table, so that they can stay moist even during droughts and dry periods.

When crayfish burrow into the ground they create “chimneys” made of mud balls that are excavated and rise above the tunnel. Burrowing crayfish may dig their tunnels on lawns and golf courses with moist soils that can be a long distance from surface waters. Lawn owners and golf course managers dislike burrowing crayfish creating holes and mounds on their turf. Pond owners worry that too many crayfish burrows can cause their dams to collapse.

What do they eat?

Crayfish are opportunistic feeders and will eat nearly any plant or animal, dead or alive. Adults generally are herbivorous and prefer to eat aquatic plants, leaves, and woody debris, whereas young crayfish are more carnivorous and prefer to eat animals such as aquatic insects, tadpoles, snails, fish, and salamanders. Both adult and young crayfish are cannibalistic.

This wide range of foods allows crayfish to be very adaptable to living in many habitats, and is important in transferring energy up the food chain. As crayfish consume dead and decaying plants and animals they provide food for smaller aquatic animals and improve water quality.

Crayfish are often found under rocks during the day, and most feed actively at night. Older crayfish usually are more active at night and on cloudy days than young crayfish. All are nocturnal, well adapted to using their antennules to “taste” and “feel” for food at night and in the dark.

How do they grow?

The hard outer shell provides protection, but limits growth. As a result crayfish get too big for their shells and regularly molt (shed) their hard exoskeletons (outer shells) to allow room for new growth. During molting a new soft shell develops beneath the old one, then the old shell splits between the carapace and the abdomen and the whole crayfish emerges through this opening. The old shell, including that covering the antennae and eyes, is left behind.

Molting is stressful to crayfish, and sometimes crayfish die when halfway out of their old shells. The new shell of the crayfish usually is soft for two to four days. At this time, crayfish usually hide because they are more vulnerable to predators and water pollution. Molting occurs six to 14 times during the first year of life when young crayfish are growing rapidly, but occurs less frequently, one to three times per year, as they grow older. Growth and molting slows or stops in winter.

Crayfish native to the United States range in size from 1 to 6 inches in length. Newly hatched crayfish are about 1/3 inch long, whereas adults can grow longer than 6 inches. The world’s largest freshwater invertebrate, the Tasmanian crayfish (Astacopsis gouldi), can grow to over 24 inches in length and weigh over 10 pounds.

How do they reproduce?

The mating season usually occurs in the fall, but can occur during other seasons for some species. During mating, a male grasps a female with his claws and transfers sperm to the female sperm receptacle. Release of the sperm from this receptacle and fertilization of the eggs are usually delayed until the following spring when eggs are released.

Females of most species lay eggs in the spring. During egg laying, the female cleans her abdomen, releases eggs from her vent, and attaches (glues) each egg to small appendages on the underside of her abdomen near her tail. A female carrying a bunch of eggs is termed “in berry,” because the eggs look like a bunch of blackberries attached to the female’s abdomen. A female may carry from 20 to over 700 eggs for two to ten months before they hatch, depending on the species and water temperatures. The egg color becomes lighter toward hatching.

During egg incubation, the female protects and aerates the eggs by tucking her tail forward and fanning the young. Females of some species are inactive during the egg incubation period. After hatching, crayfish remain attached and close to the female for safety and protection for two weeks to four months when they become independent.

Depending on the species, some crayfish mature and are ready to mate their first year, but others do not mature until their second year. Most crayfish live only about two to four years, although tagging studies have shown that individual crayfish of some species such as the Tasmanian crayfish can live 20 years. Because most crayfish live short lives, rapid sexual maturity and many eggs are important for the survival of each species.

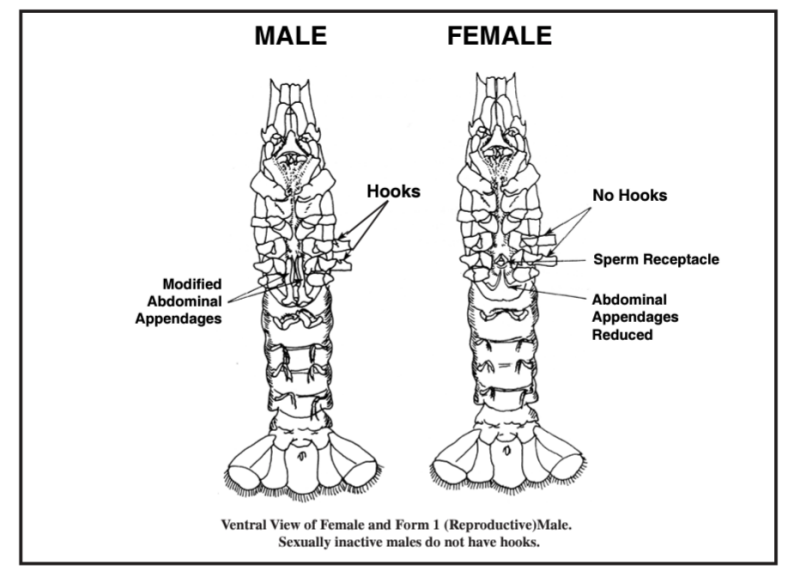

Males can be distinguished from females by the presence of gonopods, rod-like structures that extend forward between the bases of the walking legs. Females have a depressed sperm receptacle between the bases of the last two pair of walking legs.

Collecting Crayfish

Crayfish can be trapped, netted, or simply picked up by hand. Crayfish can be caught by hand after locating them by turning over rocks in stream riffles. A minnow seine can be set across stream riffles and the upstream rocks turned, scaring crayfish downstream with the current into the set net. Some collectors use a funnel-shaped minnow trap baited with fish or meat scraps, dog food, corn, or aquatic plants to attract crayfish. Because crayfish are nocturnal, using lights to collect them at night is more efficient than hunting them during the daylight hours.

In most states, crayfish are subject to fishing laws that regulate what species, how many, and where they can be harvested legally. A state fishing license usually is required to harvest crayfish. In some states, the use of crayfish for fish bait and the introduction of crayfish into natural lakes or streams are illegal. Laws against the importation and transport of crayfish are intended to limit the introduction of nonnative crayfish, some of which can eliminate native crayfish, frogs, and fish.

What Good Are They?

Crayfish are ecologically and economically valuable animals. In many streams and lakes, they are the most important link in the aquatic food chain. They eat algae, waterweeds, and aquatic animals, and are, in turn, eaten by over 240 species of wild animals. Raccoons, black bears, otters, mink, herons, and other wildlife feed heavily on crayfish. Smallmouth bass and bullfrog diets, for example, are nearly 75 percent crayfish.

Crayfish play an important role in breaking down dead plant material, and promoting decomposition and recycling. By crushing and chewing, crayfish make organic materials more available and usable as feed for smaller aquatic animals, thereby helping to link the food chain. Consider what would happen if all of the crayfish in a lake or stream were suddenly removed or killed.

Crayfish are important indicators of water quality. Many crayfish species are sensitive to water pollution, and can be used as biological monitors to forecast present and historical water quality conditions. A sudden kill of freshwater crayfish is an indicator of toxic chemicals or other forms of water pollution.

Crayfish also are a flavorful, nutritious, and valuable human food (similar to lobster) and are sold in fish markets throughout the world. Every year, nearly 80,000 tons, valued at more than $200 million, are produced in the United States alone. Crayfish are trapped in the wild and farmed in ponds in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas to be sold as food or fish bait.

Crayfish Killers: Threats

About 65 of the 400 crayfish species in North America are endangered, and 195 native crayfish species are in need of protection. These numbers are best estimates only. Honestly, no one knows the exact status of crayfish endangerment or extinction rates in the United States or elsewhere because very few distribution and population surveys have been completed.

For crayfish and other aquatic animals, habitat loss (sedimentation, siltation, dams, in-stream gravel dredging, water pollution, and the removal of submerged logs, rocks, and plants) is the leading cause of extinction and population declines. The introduction of exotic nonnative crayfish and other animals is the second leading cause for declines in numbers and species.

Nonnative crayfish are a major threat to aquatic biodiversity, causing the decline of native crayfish, fish, amphibians, and water plants. Nonnative crayfish are those that come from other countries, other states, or other river systems and lakes.

Most states have laws prohibiting introductions of nonnative crayfish, which sometimes are introduced illegally or escape from bait anglers or from pet aquariums.

Nonnative crayfish cause declines of native aquatic plants and animals through the spread of diseases, such as crayfish plague, to native crayfish; by predation on eggs, young fish, amphibians, and native crayfish; by out- competing or preying on native crayfish; and by the elimination of native water plants and habitats. The rusty crayfish (which is native to four states, but has been introduced into 24 states) is an aggressive crayfish that has been linked with the decline of native crayfish and other aquatic species in states where it has been introduced. If you collect crayfish for an aquarium or nature study, please return them to the same waters from which they were captured.

Many native crayfish have a limited geographic range. Some species of crayfish are found only in one location in one river system where only one pollution spill could cause their extinction.

Crayfish Web Links

- Rusty Crayfish: https://www.invasivespeciesinfo. gov/profile/rusty-crayfish

- Tasmania Giant Crayfish site: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tasmanian_giant_freshwater_crayfish

- Missouri’s Crayfishes: https://nature.mdc.mo.gov/ discover-nature/field-guide/crayfishes

- The Crayfish of North Carolina: https://www.nc-wildlife.org/Learning/Species/ Crustaceans

- Kentucky Crayfish: https://www.uky.edu/Ag/CritterFiles/casefile/ relatives/crayfish/crayfish. htm

- Crayfishes of Mississippi: https://www.srs.fs.usda. gov/crayfish/info.php

- An updated classification of the freshwater crayfishes of the world: https://doi. org/10.1093/jcbiol/rux070

- Crayfish of the United States and Canada: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/wetland-and-aquatic- research-center-warc/science/american-fish eries-society-crayfish- united

- Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries List of Native and Naturalized Fauna of Virginia (April 2018, includes 33 native and introduced crayfish species): https://www.dgif.virginia.gov/ wp-content/uploads/virginia-native-naturalized- species.pdf

Acknowledgments

Nancy Templeman (Virginia Cooperative Extension) and Michelle Davis (Virginia Tech Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation) provided editorial reviews of previous versions of this publication. Additional support was provided by Randy Rutan and Hilary Chapman (National Conservation Training Center, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.) Virginia Master Naturalist volunteers David L. Gorsline, Mary Klein, Jim Lefler, and Debbie Meinholdt reviewed and edited the current version.

Art illustrations by Sally Bensusen, Mark Chorba, Scott Faiman, Karen J. Couch, and Keven Peer.

Reviewed by Michelle Prysby, Virginia Master Naturalist Program Director, Virginia Tech

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and local governments. Its programs and employment are open to all, regardless of age, color, disability, sex (including pregnancy), gender, gender identity, gender expression, genetic information, ethnicity or national origin, political affiliation, race, religion, sexual orientation, or military status, or any other basis protected by law.

Publication Date

March 24, 2020