Aphids in Virginia

ID

444-220 (ENTO-617NP)

Description

Aphids, also called plant lice, are small, soft-bodied insects (Fig. 1). Aphids feed in clusters and generally prefer new, succulent shoots or young leaves (Fig. 2).

There are hundreds of different species of aphids, some of which attack only one host plant while others attack numerous hosts. Most aphids are about 0.1 inch long (2.5 mm). Generally green or black in color, aphids can also be gray, brown, pink, red, yellow, or lavender. A characteristic common to most aphids is the presence of two tubes, called the cornicles, on the back of their bodies. The cornicles secrete defensive substances to protect against predators. In some species, the cornicles are quite long, while in others they are very short and difficult to see. Some species are called woolly aphids; they are covered with white, waxy filaments produced from special glands. Often there is a mix of winged and wingless aphids in the same colony.

Habitat

Aphids are common pests of nearly all indoor and outdoor ornamental plants, as well as vegetables, fruit trees, and field crops throughout the U.S. and the world.

Life Cycle

Aphids have unusual and complex life cycles that allow them to build up enormous populations in relatively short periods of time. Most species overwinter as fertilized eggs glued to stems or other parts of host plants. Nymphs hatch from these eggs and develop into wingless females known as “stem mothers.” There are no male aphids present at this time and the stem mothers reproduce parthenogenetically (without mating). Eggs are held within the bodies of the stem mothers until they hatch, so those young are born alive. All of the offspring are females, which soon mature and begin to reproduce in the same manner. This pattern continues as long as conditions are favorable. A dozen or more generations of parthenogenic generations are typical in Virginia. Periodically, some or all of the young develop wings and migrate to other plants. Some aphid species always settle on the same species of host plant, but others have one or more alternate host plants. Male offspring appear in the fall when days are shorter and temperatures are cooler. After mating, females in the fall generation lay fertilized eggs that overwinter and hatch stem mothers the following spring.

Certain species of ants sometimes protect colonies of aphids (Fig. 3). The ants gather up aphids or their eggs and keep them through the winter sheltered in their nests. In spring, the ants transport these aphids to appropriate food plants where the ants protect the aphids from enemies and transport them to new plants at intervals. In return, the aphids provide the ants with honeydew, a sugary substance that aphids secrete as a waste product.

Damage

Aphids feed by sucking up plant juices through their beaks inserted in plant tissues. Light infestations are usually not harmful to plants, but heavier infestations may result in leaf curl, wilting, stunting of shoot growth, delay in production of flowers and fruit, as well as a general decline in overall plant vigor. Some aphids are also important vectors of plant diseases and transmit pathogens to the host plant via the saliva injected during feeding.

Aphids secrete honeydew, which may collect on lower leaves, outdoor furniture, cars, and other objects below feeding aphid colonies. Honeydew often attracts ants, bees, or flies that feed on the sugary liquid. Honeydew also encourages the growth of fungi known as sooty molds (Fig. 4). Dark coatings of sooty mold are unsightly and can interfere with the photosynthesis of any coated plant leaves.

Common Aphids in Virginia

White Pine Aphid: Large dark colored aphids with white stripe on the back and noticeably long legs. White pine aphid is a common pest of eastern white pines. Colonies occur most commonly on twigs and stems where their feeding may kill patches of the bark. Severe infestations reduce the growth and may even kill small trees. Needles and twigs are sometimes completely covered with sooty mold. White pine aphid eggs are laid in straight lines on needles. These may hatch when infested white pines are brought indoors as Christmas trees.

Giant Bark Aphid: Large ash-gray aphid with regularly spaced black spots on the abdomen. This is our largest aphid species at nearly 0.5 inch (13 mm) long including the legs. They are found on the bark of small twigs and branches of willow, maple, elm, oak, birch, and several other common deciduous shade trees. Bees, wasps, and flies are attracted to the honeydew they secrete.

Green Peach Aphid: Generally a pale yellow-green aphid (Fig. 1), but it can be darker green or pink. This species attacks dozens of different hosts including aster, catalpa, crocus, dahlia, English ivy, iris, lily nasturtium, pansy, rose, snapdragon, tulip, and violet, as well as many garden vegetables and some fruit trees. Green peach aphids transmit over 100 different plant viruses.

Chrysanthemum Aphid: Shiny, dark brown aphid with short, prominent cornicles. Common and widespread on chrysanthemum, its only known host plant in North America, where they stunt plant growth and distort the leaves.

Rose Aphid: Green or pink aphids with black legs and cornicles (Fig. 5). A widespread and common pest of all cultivated roses, this species may also damage pyracantha. Feeding damages stems, buds, and young tender leaves.

Woolly Alder Aphid: Plump bluish-black aphid completely covered with white waxy filaments (Fig. 6). Silver maple is the primary host plant, but these aphids migrate to alder in mid-summer and return to silver maple in late fall. This aphid is not particularly injurious to either host, but it is a cosmetic nuisance pest on heavily infested trees.

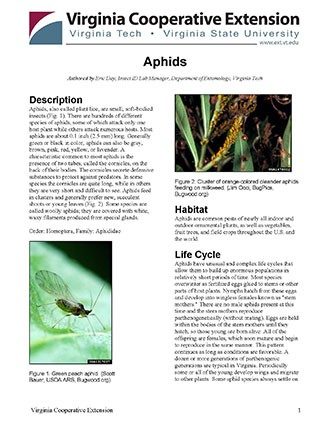

There are many other aphid species found in Virginia, some of which produce plant galls. Included in this group are Witchhhazel Cone Gall Aphid, Spiny Witchhazel Gall Aphid (Fig. 7), and the Elm Cockscomb Gall Aphid (Fig. 8). These aphids induce their host plant to grow a specialized, abnormal growth (the gall) to house and feed the developing aphid colony.

Non-toxic and Least Toxic Control

Natural enemies play a very important part in controlling aphid populations and limiting their damage. Lady beetles, lacewings, damsel bugs, flower fly maggots, certain parasitic wasps, birds, and fungal diseases all attack aphids.

Aphids attacked by tiny parasitic wasps turn into aphid “mummies,” where their swollen bodies turn into rigid, tan shells (Fig. 9). Small circular holes in the mummies indicate where an adult parasitic wasp has emerged from the body of its host.

Insecticides used for aphid control are also harmful to beneficial arthropods in the garden. Gardeners should avoid the use of insecticides whenever possible. Instead, wipe down infested stems and leaves to physically crush and remove aphids. Use a strong stream of water to knock aphids off the stems and leaves of strong, sturdy plants. Keep plants healthy and growing vigorously since migrating aphids are attracted to the unhealthy yellow-green color of struggling plants.

Chemical Control

Horticultural oil or soap can be used against aphids when found. These materials are also effective against large numbers of overwintering aphid eggs. Ask your Cooperative Extension agent for information about appropriate pesticides, including when sprays should be made.

Many contact and systemic insecticides are labeled for the control of aphids; see the Virginia Pest Management Guide for Home Grounds and Animals for the most current insecticide recommendations. Again, it is often best to leave control of aphids to natural predators to minimize damage to host plants or beneficial insects.

Revised

Olivia C. McCraw, June 26, 2014; Theresa A. Dellinger, 2019 and 2 July 2025.

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

August 26, 2025