Legacy Planning Stories

ID

CNRE-50NP

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to the following people for their contributions to this publication.

Paul Catanzaro, University of Massachusetts Amherst Adam Downing, Virginia Cooperative Extension Jim Finley, Penn State University

Jonathan Kays, University of Maryland Extension Jessica Leahy, University of Maine

Dave McGill, West Virginia University Extension

Mike Santucci, Virginia Department of Forestry

Mary Sisock, Vermont Woodlands Association Fellow

Amanda Subjin, Delaware Highlands Conservancy

“We come and go, but the land is always here. And the people who love itand understand it are the people who own it — for a little while.”

– Willa Cather

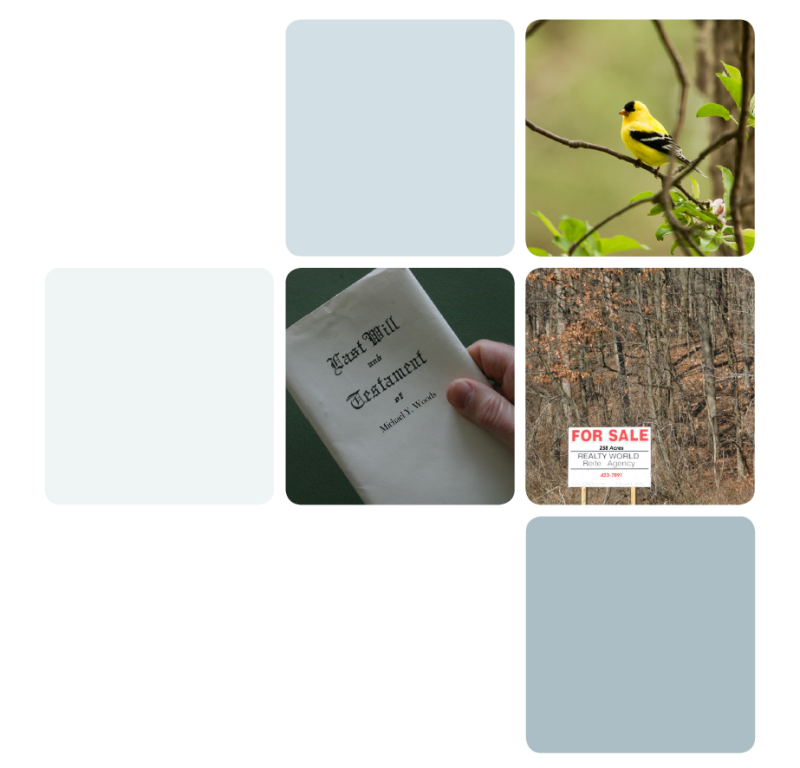

LEARNING FROM LANDOWNERS “LIKE ME”

A collection of stories about fellow landowners like you, the legacies they are creating, and how they are planning for the future of their land.

The current owners of woodlands-individuals, families, partners, and more-work to ensure that their woods are cared for well. Many have spent years investing time, money, and sweat, making decisions, and leaving their mark on the land. Yet the question of “What happens after me?” is always a looming pressure. For those landowners who act as good forest stewards, how can they ensure that, in the future, their property will be owned and managed as they intended?

Legacy planning, also called succession planning, helps landowners make well-informed decisions about how best to ensure continued stewardship of their woodlands through intergenerational transfer, land protection strategies, or other tools relevant to keeping woodlands intact. It encompasses defining and communicating future intentions, as well as legal estate planning actions. Legacy planning can help ensure private forestland will not be converted to non‐forest uses, that fiber supply and non‐timber forest benefits can remain available, and that the forest will go on to benefit future generations. Planning aids the continued stewardship of the individual’s property beyond their tenure and their beneficiaries’ tenure.

We believe you will benefit reading these stories from people like you, who have experienced similar situations, and that what you learn will help inform your own legacy planning decisions.

Legacy planning is often not easy or fast. It involves in-depth communication with heirs (if that is the way the landowner chooses to go), consultation with legal, financial, and conservation experts, decent outlay of costs to hire the correct resource professionals and create the legal and financial tools necessary, as well as a great deal of time and commitment. Many landowners haven’t yet started on this journey, or have started and been discouraged by the effort it takes. But many other landowners have already tried. This collection of stories is intended for landowners (and resource professionals) to see how others “like me” chose to make decisions and implement tools that will ensure their stewardship of the land continues for many generations into the future.

What will happen to your land after you are gone? As you read these stories in which landowners like you recount their journeys and the decisions they’ve faced in forming a plan for the future of their land, we hope you are inspired to begin your legacy planning process. You’ll find examples of how forest owners have tackled issues of fairness, or disinterested heirs, which can help those facing similar challenges make sense of their own situations and stay motivated to keep working toward completing their plan. In the stories, landowners share about establishing conservation easements, trusts, and limited liability companies, donating land, and having meaningful conversations with family. We believe you will benefit reading these stories from people like you, who have experienced similar situations, and that what you learn will help inform your own legacy planning decisions.

STATE: Maine

SIZE OF LAND: 90 acres

FAMILY LINE: 2 children

TOOLS USED: No legal tools; new conversations with their one child interested in carrying on the stewardship

Several years ago, when Richard and Beth Merk asked their children if they were interested in becoming stewards of the family’s land holdings, the response was lukewarm at best. Their children were both in their twenties at the time and didn’t feel quite prepared to take on the responsibility. With fifteen years of legacy planning consultancy under his belt—including authoring a handbook on the subject—Richard says their reaction was disappointing but not entirely unexpected.

“A generation doesn’t really begin to establish their life values until about age forty,” he says, a philosophy that informs his approach to legacy planning for clients. “When they leave home in their twenties, they’re in what I call a ‘survival stage’—starting a new job or new career or new family, perhaps, and they’re just getting through. When they’re between thirty and forty, they are at a stable age. My children are both in their early thirties. And until this last year, neither one of them had any interest in the land whatsoever.”

And then, as if on cue, their daughter, Leona, approached them to revisit the conversation. Up until that point, says Richard, “any legacy planning my wife and I did focused on what did we want to have happen to the land—without any extended family interest.” Now that future is being rewritten.

Ever the pragmatist, and with all the experience that comes from a career in financial planning, Richard embraced his daughter’s decision with guarded optimism. “We let it settle, and after a little while I kind of challenged it. I asked her if it was for financial reasons or because she feels connected to the land and has an ecological interest in it.”

“...any legacy planning my wife and I did focused on what did we want to have happen to the land...” Now that future is being rewritten.

Leona insisted it was the latter. “For as long as I can remember, my dad has always been committed to stewardship,” says Leona. “This is reflected in his leadership in forestry, the church, and the community; he also taught us this at home in the simple lesson of leaving any space ‘the way we found it, if not better’ for the next person. My appreciation for this philosophy and my passion for my parents’ property has never changed. The difference now is that I am transitioning from that ‘survival stage’ to a place where owning property is an opportunity instead of an impractical responsibility.”

The key to their success, of course, will lie in how effectively the values of mindful silviculture can be passed between these generations—the strategies that bear holistic benefits, both economically and in the interest of a healthy ecosystem. “It’s not just a question of what’s of lesser value,” says Richard, a former president of Maine Woodland Owners (formerly SWOAM), “it’s also a question of which trees provide food for wildlife, or protection. The other thing is, a healthier forest will actually store more carbon, which is ecologically one of the things we think the earth needs.”

And yet the idea of a healthy ecosystem isn’t exclusive to nature. “When my wife and I looked at our land, we came to the conclusion it wasn’t land that necessarily needed to go into a land trust. It isn’t land that has special historical or ecological significance, and so it doesn’t deserve to be limited in its future uses by some kind of conservation easement. Parts of it should be environmentally protected, and parts are likely better used for future suburban growth, since road utilities and frontage already exist.”

The Merks moved to Maine from Pennsylvania in 1980 with the intention of subsistence farming, acquiring ninety acres that included a thirty-acre apple orchard. But as Richard’s career introduced ever more opportunities, the land evolved into a passion, rather than a full-time commitment. What’s more, they had acquired the orchard about the same time that there was a glut in the global apple market, which depressed the crop’s prices. The apple trees were eventually cut down, and the Merks began to focus on best practices for managing the woodlands.

Prior to their purchase, the land had been high-graded, with all the valuable trees cut for market, leaving little volume for future growth. Since then, the Merks have allowed the remaining timber to mature, with several pre-commercial thinnings, harvesting mature trees while clearing out less desirable ones that competed with the growth they wanted to preserve. Thirty years later, the Merks are ready for their first commercial harvest. “It’ll be the first time the property’s been managed in a proper silvicultural way in probably fifty years,” Richard says.

One challenge in guiding a property’s future outside the rules of an easement is finding consensus within the family on what to develop and what to protect. “Part of our land is probably better developed than someone else’s land that has other, better conservation potential,” Richard says. But the part of his land he feels is the best candidate for development is the very same Leona wants to preserve.

“Up until now, my knowledge of the woodlands has been only high-level and not to the same extent as my parents, so as I reenter this conversation, my first focus is becoming educated,” says Leona, who works for a technology company in Boston. “It is important for me to work with experts and learn about my parents’ intentions before making any next steps.”

“If she’s willing to manage it and carry the overhead on it, I’m thrilled, because I like to think that, after spending thirty-some years on this land and hopefully improving it, that someone is going to come along and build on that improvement,” says Richard.

The fundamental concerns Leona will tackle are familiar to any responsible landowner: how to hire and manage a good technical staff; when to enlist the expertise of a forester and when to hire a logger; a familiarity with the various activities that take place at different ages of timber; and, of course, good timing.

“What I appreciate is that my parents have both given me a choice and are talking about this early. I am not finding out about this later in life or having the decision made without my input,” Leona says. “I’m lucky that my dad has the forethought to think of how the rest of us can be involved, and my sister and I can have a seat at the table if we are interested. We are starting this journey to think about what is best for the land, best for our family, and to give us all the time to learn how to make these decisions together.”

Holding family meetings and individual conversations with your children or other heirs can provide great opportunities to learn about their wants and needs, and to discuss questions, concerns, and options for the future of your land.

STATE: Pennsylvania

SIZE OF LAND: 113 acres

FAMILY LINE: 8 children, 21 grandchildren, and 25 great-grandchildren

TOOLS USED: Conservation Easement and a Limited Liability Company; multi-generational ownership and management

George Riley, his nephew David Riley, and his niece Dorie Phillips represent two generations of a family that have come to appreciate just how complex and delicate, yet how worthwhile, legacy planning for a large, extended group of owners can be. Their 113-acre property in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania is protected in ways that help them navigate its future.

The Riley property, Irish Pines Tree Farm, was originally purchased in 1937 by George Riley’s maternal grandfather, George A. Wolf. The property contains a stone farmhouse, circa 1870 or so, a barn, and a 113-acre tract historically used for agriculture. From the start, George Wolf’s daughter, Marie, and her husband, Wallace A. (Bill) Riley, took special interest in the property, planting trees, observing wildlife, tending native plants, and involving their eight children in doing the same.

From the mid-1940s on, the property served as a refuge for many family members in the midst of life transitions, such as those returning from wartime service, those relocating from one place to another, and those in need of a welcoming temporary home. It was Bill Riley who had the vision to establish Irish Pines as a tree farm, directing the planting of multiple forest stands as a weekend endeavor even though he had no ownership stake at the time. George Riley fondly remembers spending time on the property with his father and siblings on Sundays and on Wednesday afternoons when the store in Clearfield where his father worked shut down at noon, “a quaint tradition that’s gone by the wayside,” as George describes it. For years, the family would spend those days planting trees and working on “any odds and ends that Dad asked us to do.” Through these many and varied encounters with Irish Pines, Riley family members of all ages established deep connections with both the property and the emerging forested landscape.

When George Wolf undertook his own estate planning, he approached Bill and Marie about whether they would like to inherit Irish Pines. The action represented a departure from George Wolf’s practice of distributing all gifts equally, and reflected a recognition that the property was deserving of special stewardship. Through their longstanding devotion to Irish Pines, Bill and Marie had proved themselves ready for—and worthy of—the gift of this unique land, and ownership was transferred in 1970.

“He really transformed the property from a piece of land into a family homestead. It was my grandfather who established Irish Pines as a place we should really care about.”

Bill and Marie managed Irish Pines as a second home for a quarter-century. They were quite ambitious in their plans, envisioning the property as a family gathering place, a site on which to demonstrate best forest management practices, and a setting in which to educate people of all ages about conservation and stewardship. With the help of their large family, which now included 21 grandchildren, they were able to put this vision into practice. In 1993, Bill and Marie were named Pennsylvania Tree Farmers of the Year, and soon after, they recognized the need to undertake their own legacy planning to ensure the future of this place in which they had invested so much.

The first step that Bill and Marie took was to place a conservation easement on the property, which transferred the development rights to a non-profit land trust but allowed the family to retain ownership of the property itself. This easement ensured that Irish Pines could not be subdivided or developed and that its historical and rural character would be maintained in perpetuity. Importantly, Bill and Marie took this step well in advance of when the easement was needed. By doing so, they ensured that the easement terms reflected their enduring values and gave themselves the time they needed to convey these values to their heirs. These values continue to define the philosophy by which the property is managed today.

The year following implementation of the conservation easement, Bill and Marie decided to create a legal entity to facilitate ownership transfer, management, and multi-generational stewardship of Irish Pines. They involved their adult children in evaluating the pros and cons of the various options. Ultimately, they decided to establish a Pennsylvania Limited Liability Company (LLC).

The LLC concept offered the family considerable flexibility in creating an ownership and management structure that would reflect and perpetuate the Riley values. The LLC concept enabled Bill and Marie to distribute an equal share of the property to each of their eight children. “Equality among siblings was important to my mother and father,” George says.

The Irish Pines model also encourages multi-generational ownership to ensure that the legacy of the family and property will endure. All direct descendants are given an opportunity each year to join the operating membership of the LLC, up to a maximum of twenty. Currently, 12 family members of multiple generations are members of the LLC. Within the LLC, no one individual heir owns or controls the property. “If one of us wanted to opt out, there would be an opportunity to buy between us without destroying the original entity,” George explains. “At the courthouse, where your deed is recorded, the actual owner of the property remains the same, even if the ownership of the LLC changes. This structure makes it easier for a number of people to own and manage the property collectively.”

While willing to make a gift of Irish Pines to their heirs, Bill and Marie also wished to ensure that those who became involved would make it a priority in their lives. For this reason, the LLC design requires family members interested in the property to make contributions as conditions of participation. These contributions are designed to be as affordable as possible, while still requiring an annual commitment of money and effort.

Establishing an LLC can both protect the land and provide for multi-generational ownership.

For their granddaughter Dorie Phillips, the multi-generational ownership model provides a vehicle for later generations to learn about Bill and Marie and to continue to advance the educational and stewardship values they espoused. “Over many years, my grandparents invited people of all ages to visit Irish Pines, providing them with the opportunity to learn about the property’s unique forest and abundant native plants, to enjoy its tranquility, and to see a land ethic put into practice,” Dorie says. “Our structure provides a way for all interested family members to sustain the commitment to education and the spirit of inclusion that are important to my grandparents’ legacy.”

Like George and Dorie, LLC member David Riley’s relationship with the property began in his childhood, with excursions through the property with his grandfather, Bill. “Probably one of the most influential aspects of just being there was my grandfather’s impact on the rest of the family,” David says. “He really transformed the property from a piece of land into a family homestead. It was my grandfather who established Irish Pines as a place we should really care about. While we’re not going to become forestry experts, we must generally become conversant in forestry practices and forest stewardship, so as to be responsible landowners. This is important if we hope to continue the legacy that he started.” David, of course, has begun to instill that ethos among his own children, with visits to the property that include all kinds of activities, from building fires to hikes to clearing trails.

Despite the many advantages the multi-generational ownership model affords, this type of ownership is not without its challenges. As David observes, “Balancing inclusion and fairness is complicated. With so many interested parties spread far and wide, it isn’t always easy to agree on what a fair exchange of commitment and rights of ownership should look like.” David estimates that about thirty family members in all are eligible to participate in the LLC, with a few members of the fifth generation now reaching an age at which they, too, can join. With each generation growing almost exponentially, the current LLC members are grappling with how to make participation affordable, how to ensure that every member makes a meaningful contribution, and how to keep the LLC membership at a manageable size. David and George wonder whether some ownership consolidation will become necessary to enable the LLC to fulfill its purpose. The LLC also has not yet had to face a potential sale of an ownership stake. Yet for all of its challenges, this structure has been invaluable in establishing the farm as a family homestead and source of opportunities to collaborate on important work that will benefit future generations.

STATE: Vermont

SIZE OF LAND: 60 acres

FAMILY LINE: No children

TOOLS USED: Trust with the town of Sheffield as the beneficiary

While serving overseas in Germany in the early 1970s, Alan Robertson, an ROTC graduate who would eventually build a career as a civil engineer, discovered a local sport, known as volksmarching, that had a profound impact on his life. Volksmarches are, essentially, long hikes through the forest, anywhere from 10 to 42 kilometers, affording the traveler a unique way to get to know the country. Alan’s hikes led him through the forests of the Rhineland-Palatinate state, where he wound his way among the spruce and fir, the oaks and beech. “I took it up in order to lose weight and get in shape—and allow myself to drink more, because I like beer,” Alan says. But through those walks, unexpectedly, “I fell in love with forestry, and I decided that when I got back to the US, I would buy some land and try to emulate what I experienced.”

In 1978, Alan found a promising investment in 60 acres—out of a total of 800 acres that were being parceled out—in Sheffield, Vermont, whose forest shared plenty of similarities to what he’d seen in Germany. It was northern forest, what he calls “the greatest forest in the world” because of its size and resilience, with softwoods like red spruce, balsam fir, cedar, tamarack, and white pine, and hardwoods that included beech, yellow birch, and sugar maple. At the time, the land was selling for $350 per acre, though he could have bought all 800 for a hundred dollars an acre less. “The biggest mistake I made in my life was not selling my soul and just buying the whole 800,” he says, since today the land is valued at no less than $3,000 per acre. “In everybody’s life you have an opportunity to really do something unusual. And missing that was my mistake.”

Nonetheless, it goes without saying that the 60 acres he owns has enriched him well beyond the monetary value of the real estate. For the first decade or so, he spent most of his time on the land building trails, and learning about forestry in his spare time. In 1985, he enlisted a forester to help guide his projects on the land, and after retiring there in 2002, he spent another year-and-a-half finishing a house and investing in deeper ties to forestry—a passion that has led to his position as co-chair of the state Tree Farm program, as well as serving as secretary of the Vermont Woodlands Association (VWA), the primary landowner woodland organization in the state.

keep this “aimed in the direction that I want to…”

To manage the land, Alan has been following the concept of dauerwald—a German approach to forestry, loosely translated as “continuous forest,” that dates back to the late 1800s. This management philosophy was created in response to the soil decimation that had resulted from centuries of over-aggressive even-aged management. Toward the end of the 19th century, Germany realized that the pace of constant planting and harvesting was wearing out the soil. The solution was a more natural ecosystem of trees—not just softwoods exclusively—and a switch to uneven-aged management. The outcome is a forest where the mixture of hardwoods and softwoods results in a more natural forest. “You harvest no tree before its time,” Alan says. “You look for high-quality stems, and you let them grow as large as you can.”

This is part and parcel with the practice of “low-grading,” in which trees of lesser quality are harvested first—a strategy that has less immediate monetary value but is smarter for long-term management. “You take out the worst stuff, in hopes of seeing better stuff come in and also to release the good stuff you might have lurking in the undergrowth.”

The result of low-grading these past thirty years has remarkably improved the quality of the stand, which, in combination with the trails, helps ensure the integrity of the forest for generations. What’s more, in anticipation of climate change, and a warmer climate in years to come, Alan has begun planting warmer-weather species, including cherry and red and white oak—helping to assist migration of southern species to the north as the climate warms.

As for the land’s future, Alan, who is single with no heirs, has set up a trust that in its own unique way pays back to future generations the gift of chance discovery that moved him to become a landowner in the first place, during those long walks through the Pfälzerwald.

Through a trust, the land will become “the town forest of Sheffield when I get too old to put wood in the stove.” Alan doesn’t want it to be developed and wants to ensure an example for others to follow. The land is currently protected under a conservation easement, while the trustees overseeing it are a member of the town selectboard, the VWA executive director, and the NorthWoods Stewardship Center executive director.

“In Sheffield, generally, forest management hasn’t been a priority. Most folks who own any acreage here, when the trees get big enough, they’ll hire a logger and strip the land, and a hundred years later maybe somebody else will make another dollar off of it. They’ve been doing it for two hundred years. In the Northeast Kingdom, we’ve had some incredibly bad logging practices, primarily because we have huge acreages of forests.”

With this trust, Alan can set an example for new practices, with his neighbors as his beneficiaries. Among the three trustees they’ll be able to keep this “aimed in the direction that I want to, from a forest management standpoint. That’ll keep the town from mismanaging it... So, it’ll be here for a long time, and maybe people will benefit from it and learn from it and maybe do the same thing.”

Years of “low-grading”-harvesting the lesser-quality trees first-allows the more valuable, high-quality trees to grow larger and releases seedlings in the understory. “You take out the worst stuff, in hopes of seeing better stuff come in...” Alan says.

STATE: Pennsylvania

SIZE OF LAND: 275 acres

FAMILY LINE: Multiple children among 3 brothers

TOOLS USED: Limited Liability Company

David Maass’s love of the outdoors dates back to his childhood in the 1960s, when his parents would take him and his brothers on camping trips to the National Parks and Canada. His parents, both scientists, had moved to Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, from the Midwest following World War II. For them, the outdoors was more than a recreational pastime; after the loss of their young daughter, David’s mother, Eleanor, found solace through her time in the woods.

Eventually the Maass family grew weary of camping. They didn’t hunt, either. But they were restless in the suburbs of Swarthmore and wanted to maintain an intimacy with the outdoors. They bought 200 acres near New Milford for $25 an acre (using cash from savings) and anointed the land their “homeplace.” Eventually it became a profitable tree farm, which they named Butternut Tree Farm. The only thing missing, according to Eleanor, was “some sign of civilization.” With the discovery of a concrete foundation for an old barn that had since been torn down, the Maass family proceeded to build a formal home. “My parents bought a kit from Walpole Industries. In one weekend we put up a cabin, and that became the center of all of our activities.” Over the years, it grew to two stories. “My parents did all of the work themselves,” David says. “Dad did the plumbing, Mom would do the electrical work.”

“…they can make a decision based on sentimentality or practicality, but wouldn’t necessarily be based on the land being a financial burden. I’ve taken that out of the picture for them.”

By the time David was in college, at forestry school, in 1969, his parents had purchased another 75 acres near Butternut Tree Farm for $6,500. In 1992, David’s parents gifted the 75 acres to him and his two brothers. The land was worth $57,000 by then, but by portioning it out over three years, they were able to avoid any tax burdens. (At that time, federal tax laws allowed gifting a child up to $10,000 per year without a penalty.) It helped that the land fell under the Clean and Green tax program, which bases property taxes on use values rather than fair market values, allowing the Maasses to pay only $200 per year in property taxes. “That low tax level let us postpone decisions about what we wanted to do,” David says. “In the end, we decided to hang on to the property, with the thoughts of passing this on to our heirs.”

The Maass brothers conducted three timber harvests, one in 1990, another in 2004, and again in 2014. All were designed to improve the forest to focus on production of high-quality timber. The same logger and forester were involved in all three harvests. In that way, the operator can see the value of his previous work.

The Maass brothers were living in different states by the time they inherited the property—David in Maine, his twin brother in California, and the youngest in Iowa. He and his brothers were spread far and wide, David says, “it was very difficult for us all to get together.” Looking back on it, he realizes that the gift of the land was a way of bringing him and his brothers closer. “I suspect they gifted this to us as a way to force us to have to communicate.”

To this day, the Maass brothers are all absentee owners, though David visits the property about once a year. The land is mostly used for timber—hardwoods including cherry, maple, ash, and oak—while a portion of it is leased to a gas company that drills 6,500 feet below the surface. The brothers insisted on keeping the actual wells off the property, and set up a Limited Liability Company (LLC) to help manage any liability. Though the LLC was costly to form, it protects the family’s personal assets from being used to compensate for any damages from the operations on the land. The royalties from the gas extraction more than cover the cost of maintaining the property, including the cost of forming and maintaining the LLC, which ultimately ensures succession of the land to the next generation of Maass children. “This way, there’s a process,” David says, “a business in place that they can latch onto and run. Or, if they want to sell it, they can sell it.”

David’s and his brothers’ children—mostly in their 40s—are as far flung as the brothers themselves. With the disbursement among various absentee owners, they’ll eventually have to decide how best to navigate between the practicalities and sentimentality of land stewardship. “Some of our children have very emotional ties to the property,” David says, adding that his parents’ ashes were spread on the property in a small ceremony some years ago. “If our children inherited it tomorrow, I think they’d hang on to it for a few years and eventually find it too difficult to handle—simply because it’s outside their realm of expertise. But the way I’ve set it up, the land is part of an investment portfolio, which at least pays for the annual expenses,” David explains. “What’s more, no one is dependent on the income the property generates, which means we can manage it judiciously. So they can make a decision based on sentimentality or practicality, but wouldn’t necessarily be based on the land being a financial burden. I’ve taken that out of the picture for them.”

As for Eleanor’s plan to bring the boys together through the land, “In many ways, I think it worked,” David says. “It gave us something very tangible to talk about. As business partners, it requires regular conversation, so if we do nothing more than discuss what’s going on with the farm, you catch up on other things—weather, football, family affairs. Without it, we’d just fall back to the occasional e-mail, phone call, Christmas cards. So I think we’re closer for having had it.”

STATE: Maryland

SIZE OF LAND: 90 acres

FAMILY LINE: 3 children

TOOLS USED: Trust with children as beneficiaries; Conservation Easement on 72 acres

Don Grove says that even as a boy, he’d always wanted to be a farmer. The practice goes back generations in his family. After he left the Marine Corps in 1967, he found 90 acres near Hagerstown, Maryland, complete with a farmhouse—though it had no bathroom at the time. His wife, Linda, went along with it anyway. The first thing Don did after buying the farm was, of course, to put in a bathroom.

Over the next twenty-five years, he worked as a mechanic as the farm progressed. He and Linda grew crops and raised cattle. At one point they happened to read an article in Progressive Farmer about the benefits of planting trees, and that the US government had implemented a program with an incentive that assisted farmers with planting pine trees. After consulting with a state forester, the Groves planted 25,000 white and scotch pine to establish a habitat that helped revitalize the area’s deer population. In 1980, the farm became dedicated entirely to trees.

Don says the benefits of forestry were obvious from the beginning—especially for the fact that he had a full-time job. The main benefit was time. With traditional crops, farmers are at the mercy of the weather, which limits their windows of opportunity for planting and harvesting. “If you take a cornfield, you’ve got to plant it when the soil is right and the weather right and you’ve got to pick it when the soil is right and the weather is right. With hay, if there’s rain coming, you’ve got to bale it and get it in the barn, like, right now.” With trees, that window is much more forgiving. “If the weather’s not right, if you’re having a wet year, say, then you can wait until next year. As far as planting them, you can plant in the spring, the fall, both seem to work out. You don’t have to sit around and watch for the weather like you do with grain crops. And since I worked off the farm the whole time, I needed this wide window. I couldn’t tell the boss, ‘Hey I’m not going to be in for the next three days, I’m going to be making hay.’”

And the benefits of switching from traditional crops to trees were inherent in more intangible ways. “You’re growing trees to make money, but you’re also growing them for the wildlife, for the protection of the water, and because you like trees and the shade they produce. All these things go together.”

Following that ethos, the Groves decided to join the Maryland Woodland Stewardship Program, which introduces curious novices to the special commitment of forest stewardship, including concepts of succession, how trees contribute to the ecosystem, and how best to manage them to meet goals.

In 1999, the Groves started a trust that, when the time comes, bequeaths the land to their three children, with a stipulation that allows the children to sell the property. In 2006, they created an easement with the state of Maryland that protects 72 acres from development, regardless of what happens with the rest of the property. The Groves received $30,000 from the state at the time, and receive no tax benefits from the easement directly. The state also planted another 14 acres in trees. (Since then, easement agreements have evolved such that the value of easement-protected land is more in line with the current value of development rights.) And while the land will never be able to realize its monetary worth as the city of Hagerstown expands and demand for developable land increases, the Groves nonetheless emphasize the less explicit value of such a gesture.

“We’ve never said they have to keep the property; maybe it won’t fit into their lifestyle.” But they certainly hope their children—and, in particular, their grandchildren—realize the benefits of a life that’s intimately connected with the natural world.

Their children all appreciate the outdoors, they say, but “nobody’s really committed to it.” One son works in technology in Rockville, and visits the land now and then for hunting. One daughter is a physics high school teacher, married to a Navy pilot, and, as is the case with most military families, is often relocating from city to city. Their oldest daughter, a single mother, lives on the farm with her two children.

“We’ve never said they have to keep the property,” Linda says. “Maybe it won’t fit into their lifestyle.” But they certainly hope their children—and, in particular, their grandchildren—realize the benefits of a life that’s intimately connected with the natural world.

“I hope they do, so that they can give their own kids a sense of the upbringing they got to enjoy—knowing where food comes from and how it gets to the table. I think its priceless. I think that’s what’s missing today. People valuing their own lives in a way that just doesn’t happen without getting close to nature.”

Regardless of what their children decide to do, the Groves say they can at least reflect back on an experience they forged together, one that at times tested a marriage but certainly, when all is said and done, brought them closer as friends. “Back in ’68, when we bought the place, she was good enough to go with me on this,” Don says. “All it had was a kitchen sink with two five-gallon buckets underneath that you carried outside to dump out. We did have water coming to the house, but that was it. Right then and there, I got a good woman, I knew it.”

STATE: Pennsylvania

SIZE OF LAND: 60 acres

FAMILY LINE: 1 child and 3 grandchildren

TOOLS USED: Conservation Easement donated to a land protection and forest management non-profit

One doesn’t expect a Sunday morning drive to be a life-changing moment, but one such morning in 1973, Bob Slagter, driving just outside Titusville, Pennsylvania, happened to notice a handwritten FOR SALE sign tacked to a bridge. Bob was curious and called the number—it wasn’t even 9 A.M. yet. The sign had been posted just the night before. The seller, it turned out, was getting divorced and was anxious to unload the property. Bob already knew the land somewhat, having spent his boyhood fishing in nearby Caldwell Creek, which had been “a kind of sacred ground for me and my family.” Bob was the seller’s first caller. They closed the deal in a week. Looking back on it, he says, “it was meant to be.”

Bob bought twenty-five acres for $4,000 and, over the next ten years, continued to buy small parcels until he owned close to sixty acres. Since then, he has immersed himself, little by little, in the principles of stewardship, planting about 500 trees on the property—cherry, oak, sycamore, and hickory, among other species. Meanwhile, his passion for fly fishing inspired a couple of bank-improvement projects to help improve the quality of the streams, to increase the population of aquatic insects, and to guard against siltation.

After retiring in 2005, Bob joined the Pennsylvania Forest Stewards, an organization that promotes best management practices by reaching out to landowners and encouraging them to be stewards themselves, so that they not only use best management practices for their own land but interact with other landowners in order to promote these principles. Bob did quite a bit of recruiting for the Stewards’ volunteer program, and today he serves as chair of its steering committee. He also does a fair amount of writing for the Center for Private Forests and Forest Stewards. “It’s a good way for me to stay busy doing something I really love,” he says.

In addition to these commitments, Bob works with the Foundation for Sustainable Forests, an organization that acquires, protects, and manages a land parcel’s trees in order to create revenue for the future purchase—and thereby protection—of lands in northwestern Pennsylvania.

The arrangement is unique in that, rather than relying on the owner to coordinate between two entities, it combines land protection and resource management under the purview of a single organization, with all proceeds going to the Foundation for future protection efforts. This eliminates the unknowns of economic drivers, and allows for a more precise coordination of goals, making the entire process more efficient and effective. What’s more, the owner incurs none of the costs of either effort.

It also allows the Foundation for Sustainable Forests to put its philosophy of worst-first cutting into practice.

Though Bob sees the virtue of eliminating economic drivers from the equation of ownership, he also understands that trees are indeed an economic resource that can improve what’s left after the resource is removed. This is, as he puts it, the long game in land management. “If you take care of the land properly, the trees tend to flourish, and the land tends to heal and take care of itself. That gives you more marketable trees. In the end, the trees are a resource, and you want to make it a sustainable one.”

“For me and my wife, it provided instant peace of mind. All of a sudden we knew that no matter what happened, that all the work I’d done and all the work they’re doing now would go on indefinitely.”

All of Bob’s commitments—to the Stewards, to the Foundation, to his own land—might seem impractically demanding, but he finds it immensely fulfilling. “It has taught me how much I didn’t know about what I was dealing with,” he admits, from controlling invasive species to clearing the understory, from regeneration to the riparian buffer along the stream—“literally everything. And it also provided friendships that transcend forestry.”

Just as importantly, being a steward forced him to give serious consideration to his land’s future. Bob has heirs, who appreciate the land but “have no idea what to do with it.” Donating his trees to the Foundation for Sustainable Forests through a conservation easement provided the opportunity to create a legacy his children and grandchildren could enjoy while knowing he did the right thing. “For me and my wife, it provided instant peace of mind. All of a sudden we knew that no matter what happened, that all the work I’d done and all the work they’re doing now would go on indefinitely.”

As Bob sees it, the key to legacy planning is training, which extends well beyond landowners simply browsing through their options with regard to easements. “For legacy planning to really work,” he says, “the more training that’s given, not just to the individual, the better. All we have to do with individuals is get them to admit that just leaving it to the kids isn’t good enough. They have to admit that. Because chances are infinite that the property will either be split, sold, poorly cut, you name it. Any of the things you don’t want to happen will happen. So training has to be given to people in the planning business—like financial planners, like lawyers—those who are charged with helping people figure out what to do with their hard assets when they pass. People in the legal field have to see this as a service they can provide to their clients, to say, ‘Have you thought about a real plan for your property?’ Because sometimes the property is the biggest asset they have. It isn’t just about educating the owners but the professionals who advise them.”

Bob Slagter and his wife realized their heirs appreciated their 60 acres of forest, but had no idea what to do with it. By donating his trees and protecting his land through a conservation easement, he created a legacy that his children and grandchildren can enjoy without being overwhelmed with caring for the land.

STATE: Virginia

SIZE OF LAND: 575 acres

FAMILY LINE: 1 child

TOOLS USED: Limited Liability Company; have gifted a 10 percent share of the company to their child and her spouse, making them co-owners, but with the ability to “try on” what being responsible means

Preparing your heirs for land stewardship can be an intimidating process, especially if you’re unsure of whether they are willing to accept the responsibilities that come with managing it. Either way, it’s best to know where your children stand sooner rather than later, to allow plenty of time for planning.

Joel Cathey came into his ownership of 575 acres almost by accident. A timberman by trade, he was approached by his employer with an opportunity to buy into a large tract of land in Halifax County, Virginia. After consulting with his wife, Cathey bought half interest in the property in 2013. In November 2014 he was given the opportunity to purchase the other half. He and his wife placed the tract in a Limited Liability Company (LLC) named Long Branch Farm, and he’s spent most of his free time there working on improvements to the property and managing the wildlife habitat.

Joel began thinking about retirement and estate planning a few years ago, and during that time planted the idea of passing on his land to his daughter, Sharon, and son-in-law, Ryan. It was important for them to be aware of just how much land was at stake, and if they had any interest in it. To Joel, preserving their inheritance was undermined if it might become a burden, and the answer to that question rested, in large part, on whether they would be dedicated stewards. “Just because I like timberland and I think it’s a good place to put some money doesn’t mean that that’s something they should be interested in at all,” he says. “The last thing I would ever want them to think is that they ought to be interested in land simply because I’d want them to be. But I did want them to start thinking about whether owning timberland was something they wanted to commit to.”

Not wanting the task of owning and managing 575 acres to be a burden to their daughter and son-in-law, the Catheys decided to gift them a 10 percent share of Long Branch Farm LLC so that they could “put their toes in the water” to see if they are ready and willing to take on full responsibility for the land when the time comes.

“The last thing I would ever want them to think is that they ought to be interested in land simply because I’d want them to be. But I did want them to start thinking about whether owning timberland was something they wanted to commit to.”

As part of their planning, the Catheys decided the time had come to make their daughter and her husband part owners. But there was an inherent difficulty in the question. “It’s one thing to ask them, ‘Is owning timberland something you’d be interested in?’ How do they know?” he says. “In some ways, it’s a little unfair to ask that question.”

After consulting with an attorney, the Catheys gifted their daughter and son-in-law each a 5 percent share in Long Branch Farm LLC in March of 2016. “It was a way of letting them put their toes in the water, and at least maybe start feeling like they own some land. We’re trying to include them in all the management decisions that we make about the property.”

“We now feel a sense of ownership, even with just that 10 percent share,” his daughter, Sharon, says. “We feel a responsibility to keep what he has been working toward going for as long as we can.”

The Catheys had considered putting a conservation easement on the property, but decided against it. “I’ve seen where conservation easements did a really great thing, a real service to a family, so I’m not against them in the least. But I don’t feel that in our situation a conservation easement is something that we would be interested in.” His reasons are varied, he says. For one, “I don’t feel like the properties we own have that big of a development potential. The difference between its development potential and its value isn’t that great, so the dollar value of a conservation easement isn’t that great. The other reason we’re not for it is, we don’t want to leave our daughter and son-in-law something and say, ‘This is for you. We want it to be yours, but we have taken some of the value out of the place and you can’t do this and you can’t do that with it.’ We’re not interested in that at all. And it doesn’t mean we’re against conservation easements in general.” In lieu of the easement, Joel says that the leasing out of other parcels—for farming, for hunting—helps cover the tax burden.

As for the land that’s been gifted to Sharon and Ryan, Joel says it will be their choice whether a conservation easement would be right for them. “But it’s going to be their decision. We’re not going to make it for them.”

STATE: West Virginia

SIZE OF LAND: 160 acres

FAMILY LINE: No children; land will go to nieces and nephews, but no legal tools in place for the transfer

TOOLS USED: Conservation Easement

As a vice president of the Cacapon & Lost Rivers Land Trust, which protects nearly 14,000 acres of watershed in West Virginia’s eastern panhandle (the largest land trust in the state), Bob Poole has an intimate understanding of what makes land worthy of serious conservation efforts.

“We don’t accept just any piece of land to be protected,” he says, “because it takes as much work to protect fifty acres as it does 500.” Since its founding in 1990, the Trust, whose mission includes the preservation of forests, farmland, and the area’s rural heritage, has acquired fifty-one easements, though it has not accepted all of the proposals it has received in all those years. Bob says the criteria are higher than most people assume. “A lot of people will come to you with one or two acres they love very much, that’s been in the family for years,” he says. “But it doesn’t qualify because of any number of reasons. All land has value for some purpose, even a gravel pit or a quarry. But that’s different from what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to preserve land that has some special conservation value—the trees, the insect life, the water, the plant life—in short, its biodiversity.”

Bob and the Trust pay particular attention to this last quality, prizing the ecosystem as a whole as much as the flora that sustains it. “And there are many items to consider along these lines, some of which are more important than others. If you have a piece of property that has endangered life of one form or another on it; if the property lies along a river; if it connects other protected lands; if it’s threatened. And you have to ask fundamental questions, like how is the land going to change as global warming takes place over time? And what is the diversity of the landscape? What defines its resiliency? This is how we measure the value of a landscape. And it makes a big difference how big a piece of property is.”

Bob himself owns about 160 acres in Morgan County, West Virginia, which he purchased in 2001, and which he protected through a conservation easement managed by the Cacapon Trust in 2007. He is especially proud of the ecosystem that has flourished there over the years—a parcel that’s not only rich in oak and hickory (not to mention maple, pine, and even cucumber trees) but is teeming with bobcats, bears, bald eagles, otters, rattlesnakes, and the increasingly rare whippoorwills, wood turtles, and Allegheny wood rats.

He got to know the land he owns during his boyhood, hunting with his brother and a neighbor, bringing home squirrel, deer, grouse, and turkey. A retired pilot, Bob still hunts deer in West Virginia during the fall. “Hunting is an important tradition in West Virginia,” he says. “It’s a huge historical heritage for its people.”

Bob spent two years as a soldier in Vietnam, and later eighteen years in Saudi Arabia as a corporate pilot, flying 737s and Gulfstreams for various clients, returning to Washington, D.C., in 1996, where he flew out of Dulles until his retirement in 2006. All the while, he would visit the Morgan County parcel during long breaks at home. In many ways, he says, no matter where he’s been, that land has always been with him.

“I think of this land as an old friend I’ve known for sixty-five years,” he says. “I have a relationship with it. I’ve gotten so much out of it, in all kinds of different ways—both spiritually and in terms of the food provided, whether its mushrooms or pawpaws or wild game. I think like everybody does about an old friend, you want to take care of that old friend when you’re dead and gone. That’s what the conservation easement does.”

Bob is passionate about the virtues of conservation, but as someone who works on the land trust side of the equation, he also understands why families may choose to forgo the process.

“...someday there won’t be anyone related to me who knows this land very well or knows its significance or loves it as I do. But then, with the easement, I don’t ever have to worry about such things.”

“Probably the biggest obstacle we run into is that many big pieces of property are owned by a family. And when you have an old family, there are many heirs, and they all have to agree, and they don’t all agree. They may disagree about what to do with the property. The best scenario is one owner, or two. Then you can make some progress.”

There is, too, a relatively new phenomenon he’s noticed. “In the political environment we have now, many people don’t want the government involved in anything they do. But more to the point, in this part of the country, you have people who have been on their property for many years. They’ve grown up on the land with no restrictions, and they don’t want anyone telling them what to do. And of course, when you come in as a trust, they think maybe you’re working for the state or the county—you’re an institution, or a corporation. So they naturally have a resistance to it. It makes them nervous. And that’s why we have people on our board who are old ranchers and farmers whose families go back seven generations in West Virginia. And we go out of our way to have people on the board who were born and raised in our watershed. It’s important to build that kind of trust.”

Bob and his wife, Pamela, do not have children, so they’ve decided to bequeath their land holdings to their niece and nephews. And while he hasn’t stated it outright or made it official through any legal proceeding, “it has become apparent over the years that we’ll leave this property to them. We haven’t sat down and had that conversation with them yet, but it’s important to take that step, to sit down with everybody and let them know what you’re doing. A family conversation.” Bob says his nephews have built their own connection with the property through family excursions and hunting, and that they’re ready to return the favor of the memories it has given them through stewardship.

As important as the conversation about stewardship is, Bob takes a much longer view on things—a view that accounts for the randomness of bloodlines and unpredictability of family dynamics, where the legal protection is a necessary step toward a legacy. Generations look at land differently; the easement protects its natural integrity.

“This family I’m a part of will expire someday. And while it might not be in a hundred years, or two hundred years, someday there won’t be anyone related to me who knows this land very well or knows its significance or loves it as I do. But then, with the easement, I don’t ever have to worry about such things.”

For some landowners, a conservation easement provides a way to care for the land after their tenure. “I think of this land as an old friend...,” Bob says. “I think like everybody does about an old friend, you want to take care of that old friend when you’re dead and gone. That’s what the conservation easement does.”

STATE: Pennsylvania

SIZE OF LAND: 300 acres

FAMILY LINE: No children

TOOLS USED: Conservation Easement donated to the state; Remainder Sale to neighbor with invested sweat equity

At its core, land stewardship is about connection—with the natural environment, of course, but also with those who share in the responsibility of caring for it. Often that responsibility is bequeathed to future generations of one’s own family, but that isn’t always the case. In some instances, a shared connection to a piece of land is almost as strong as blood.

Such is the case with Armin Behr and Bob McConahy. The two men met in 1973, after Behr bought the tract abutting the McConahy farm. Bob was just sixteen at the time. His father, Clarence, was a dairy farmer who rented the farm they lived on. Clarence and Armin quickly became good friends, and Bob remembers fondly a youth that included plenty of weekends hunting and camping on Armin’s property, which lay just to the north.

Behr had found the property—just over 300 acres in Pennsylvania’s Bedford County—almost by accident, after months of searching in vain in western Maryland. (Stopping in Bedford, he happened by a realtor’s office, and saw a picture of the property for sale there in the window.) Armin’s attraction to the land was as practical as it was sentimental. “It was originally an investment strategy,” he says. “Land was pretty good speculation back then. But I also had a desire to have a place of my own so I could enjoy nature.” Growing up in Queens, New York, Behr was a city kid who nonetheless had fostered a respect and attachment to nature through weekend hiking trips near Port Jervis. His eventual career in the science industry led him westward to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where, on days off from his work for the Atomic Energy Commission, he nurtured a passion for mountain climbing, and even bought 1,100 acres near Las Vegas, NM.

A job with the US Department of Energy brought him back East, where he settled in Bethesda, Maryland, and eventually recommitted himself to conservation through the purchase of the Bedford County property. He enrolled in forest stewardship classes at Penn State and learned what he could about forestry and best management practices. And, of course, he kept up with the McConahys.

In 1985, Clarence McConahy died of a heart attack. Bob was married at the time, living in nearby Somerset County. He returned to the farm to help his mother as much as he could, but after a couple of years it had become clear that the farm was simply too much for her to maintain, and she moved off the land to live in an apartment nearby. Plus, after Clarence passed away, the farm was sold to a new owner with intentions to renovate the structures. Despite several attempts to buy the land over the years, Bob says it just never worked out.

“I wanted Bob to know he was going to be the future owner, for his own peace of mind. I wanted to relieve him of that uncertainty.”

Not long after his mother moved off the farm, Bob approached Armin and asked if he would sell him a small parcel of land, so that he could at least be that much closer to the place he considered home. Armin sold him eight acres through an arm’s length transaction, “out of gratitude to Clarence,” he says, “who was a very good neighbor to me.” Bob, a union carpenter by trade, built himself a cabin. Shortly thereafter, Armin hired him to build him a house on the Bedford County property for his retirement. And the projects kept coming—rebuilding the barn, repairing the machine shed and other structures, building fences, improving the access roads, and clearing and preparing the fields for farming. Over the course of twenty years, they developed not just a fine-tuned working relationship, but a friendship very much like the one Armin shared with Clarence all those years ago.

With such intense commitment and attachment to the land they shared, it was inevitable that Bob would want to find a way to protect all of what he’d invested in it—not just his sweat and money (he and Armin both covered the cost of various materials), but a guarantee on his emotional investment as well. This was, after all, a place filled with a lifetime of memories and labors.

As a result, Armin’s legacy planning took an interesting turn in recent years. He was well aware of Bob’s commitment to the property, but also knew that Bob didn’t have the means to buy it outright. Armin therefore arranged a remainder sale, which follows the protocols of any normal sale of property—in this case, however, Armin continues to pay the property taxes, and holds lifetime usage rights to the property. Upon Armin’s passing, the property and all rights to it are immediately and automatically transferred to Bob. “This makes it much easier for us to work together, since anything he does to improve the place—which I don’t pay him for—he benefits from anyway.”

Sometimes, a combination of legacy planning tools works best for landowners and those they want to care for the land after their tenure.

“I took a big chance,” Bob says of his years of sweat equity. “I figure I had over a hundred thousand dollars invested in that property, and I could’ve lost all of that. At one time, my wife would even warn me, ‘This could end up like your dad.’ And I just had to face it, the way Armin and I were. I was just determined that it wasn’t going to fail. But you know, Armin is a unique guy—and I could see that. I’m speaking out of turn here, but I’m thinking he thinks that about me. I think that’s why it worked out.”

In 2007, Behr donated an easement (excluding a little over ten acres where structures had already been built) to the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) Bureau of Forestry. The land is divided into three categories of use. The first is forest, roughly 240 acres of mixed hardwoods—oak, maple, hickory. Another portion has been enlisted in the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, through which farmers are paid to manage fields for wildlife habitat and promote warm-season grasses. The third portion of the land is dedicated to beef cattle.

Bob, now sixty-five, says that both his children and grandchildren have taken an active interest in working the farm and caretaking the land—a promising legacy of commitment that gives Armin peace of mind. As to why Armin chose to make this transaction now—instead of including it in a will or as part of an estate, he says, “He really loves the land—the forest and the living things—and will continue to manage it much as I would have. I wanted Bob to know he was going to be the future owner, for his own peace of mind. I wanted to relieve him of that uncertainty. It’s definitely an innovative approach.”

STATE: Virginia

SIZE OF LAND: 1,000 acres

FAMILY LINE: Grandchildren and great-grandchildren

TOOLS USED: Limited Liability Company with many generations involved in the management of the land

In strategizing ways to preserve her family’s nearly 1,000 acres of farm and forest in Brandy Station, Virginia, Cecilia Schneider-Vial realized she had a unique advantage—history. The property, called Berry Hill, was the site of a skirmish during the Civil War. (The original farmhouse was destroyed by Union troops during the war. The house that replaced it, in 1864, still stands today.) Cecilia is a member of the Brandy Station Foundation, an organization that works with the Civil War Trust, and she invited several historians to give lectures on the property during the war’s sesquicentennial anniversary, in 2011 during Culpeper County’s Harvest Days Farm Tour. But the war is only one historical attraction; another is the fact that Berry Hill holds a natural spring, which was once the source of a popular bottled mineral water sold more than a century ago, and which the family hopes to someday bottle and sell again.

Then there is the land’s natural attraction, which they cultivate by hosting tours by the Virginia Department of Forestry that focus on community woodland education, and a Culpeper County farm tour, which introduces consumers to farms around the county in an effort to encourage more support of local growers. The tours, it seems, are just the beginning; there are even plans for devoting a portion of the land to a solar farm. “There’s a lot of potential here,” Cecilia says. “With a little bit of imagination, you can go for all of it.”

After their father died in 2007, Cecilia and her sisters began to plan seriously for the future. They agreed on the importance of preserving the land, but they didn’t want to force future generations into easements and other restrictive agreements. “We were hoping to instill enough love of the land and the surroundings that they wouldn’t just sell it for development,” she says.

A commitment to the land must therefore be balanced with a commitment to the concept of freedom of choice.

With that in mind, in 2009 they set about exploring all the ways in which the property might become more dynamic than just a parcel to protect. Part of the plan, of course, included generating enough income such that the land could pay for itself. This included leasing a portion to a neighboring farmer, who rotates soybean, corn, and wheat crops, as well as harvesting trees such as loblolly pine, oak, ash, and black walnut on 700 acres. That same year, the family began developing a nature trail along the edge of the property, along a creek known as Mountain Run, and discovered a portion of the old Fredericksburg Plank Road in the process.

Today, six grown grandchildren and three great grandchildren are involved in the property’s management. Imagination seems to be the key, insofar as it encourages stewardship through various points of interest, rather than insisting on a more straightforward—and perhaps tedious—form of conservation that might not be palatable to younger generations. “It’s a very personal decision,” Cecilia says. “Some people want to make sure that nothing, in perpetuity, will ever happen to their property, that it will always be set aside for nature. And some people just see the dollar signs.” Influencing their strategy is the fact that the family’s background is also widely varied. Cecilia’s father was Chilean, her mother is from the American South, her husband is Chilean; she and her siblings were born in New York City; her brother-in-law, meanwhile, is Japanese. “There’s a culture mix that leads us, perhaps, to always thinking the American way. For us, and the next generation, to oblige them to be locked into this—well, it’s a fit that depends on the family itself.”

In foregoing a conservation easement and keeping the land strictly under the protection of a Limited Liability Company (LLC), Cecilia is honoring perhaps contradictory principles. Or at least, they’re managing a tension between impulses. On the one hand, she says, to predetermine a land’s intrinsic or monetary value in perpetuity seems a bit selfish. “We are stewards of this land,” she says, adding that her family’s values toward the land reflect aspects of their legacy from their parents. “So we’re taking care of this land, but it isn’t ours forever.”

But while hoping to protect the land’s ecological integrity, the family is also staying true to the commitment that if the next generation chooses to develop it, they should be at peace with that choice. “I wouldn’t feel happy about it, but I’d have to honor it,” Cecilia says. A commitment to the land must therefore be balanced with a commitment to the concept of freedom of choice. “Hopefully, thanks to our guidance, we can’t control what they do in the future, but we’re trying to follow the way we think it should be and instill in them the same feeling. So far, we all seem to be on the same page. Down through the generations.”

Like Cecilia Schneider-Vial and her siblings, some families with many grandchildren and great-grandchildren may choose to forgo forcing restrictive agreements to preserve the land on future generations and instead rely on the love of the land and stewardship instilled down through the ages.

STATE: New York

SIZE OF LAND: 200 acres

FAMILY LINE: 2 children, 8 grandchildren

TOOLS USED: Conservation Easement and an Irrevocable Trust with children named as beneficiaries

In some cases, inheriting land comes with the implicit mission of starting over. Kenna Levendosky’s 200 acres near New York’s Delaware River, near the town of Delhi, might arguably be a case in point. She inherited the property after her father passed away in 2008. With it came a house that was a couple of centuries old and in need of repair, to which she and her husband have dedicated themselves. The land itself was in need of restorative care, its timber having been harvested by her father with good intentions but without a strategy for regrowth, since he didn’t have the background or access to expertise that might have helped him harvest smarter.

“My parents did not have any particular game plan with the land except for survival,” Kenna says, recalling how her parents moved to New York from Wyoming soon after they were married. The land was purchased by her grandparents as an enticement for her mother to move back East, and the plan worked; soon after they arrived, her parents settled into a new life—her mother as a schoolteacher, her father as the manager of a milk-processing plant. And while they didn’t farm the land for profit, they did use timber harvests as a way of building up equity. “It was what they had to survive on,” Kenna says. “In those days, people didn’t have 401(k)s and that sort of thing.” There were three harvests in all, starting with ash (sold to a baseball bat factory), then moving on to the rest of the hardwoods, including oak and, finally, the 300 maples that the family had once tapped to make syrup. It wasn’t until late in life, after he’d partnered with Delaware Highlands Conservancy, that her father learned about best practices and how he could have managed the harvests better, and felt deep remorse for not having done so. “My father didn’t have the training,” Kenna says. “He hired a forester who was a slash-and-burn kind of guy. So the land is in recovery mode now.”

Kenna is a firm believer in the fact that a forester—the right forester—makes all the difference in the world. “Some of them work for commercial companies, and may not be ecologically-minded,” she warns. “But if the landowner is educated to that fact, not only do they make a better profit—because these guys will want to take a huge percentage of the profits—but your forest continues in good shape. Once the process starts, the forester makes a lot of decisions along the way. So that’s key.”

As more and more developers approached her father about building, he finally did some research and reached out to Delaware Highlands Conservancy, and arranged an easement on the land that introduced a model for best practices and now all but guarantees its protection against encroachment. With its proximity to New York City—and, as a result, consistent pressure from real-estate interests—the Conservancy has been a vital asset. It helps, too, that Kenna herself is dedicated to the principles of ecology, values she inherited from her father. Through his passion for hunting and fishing, bringing Kenna along on countless outings on their land, her father imparted a reverence for nature, which eventually led her to complete a master’s degree in ecology at Penn State.

Setting up an irrevocable trust can ensure that medical and other expenses will not interfere with the transfer of property.

While they didn’t farm the land for profit, they did use harvests as a way of building up equity. “It was what they had to survive on. In those days, people didn’t have 401(k)s…”

Kenna continued her education in best practices through Delaware Highlands Conservancy’s programs—in particular, Women and Their Woods, an initiative that supports the growing number of women in need of community and resources in a traditionally male-dominated culture of land ownership and management. “It has filled a gap and has offered a place for women who have inherited land or who are in this position of caretaking land to ask questions without judgment,” Kenna says.

Armed with this expertise, she’s been a passionate steward of her inheritance, and has done much toward investing in the land’s future prosperity. She and her husband have been establishing a foundation for future old growth by planting various species of trees, including apple and walnut, and clearing trails that reach toward the end of the property to make surveilling it easier.

With the land’s future in mind, Kenna has already set up an irrevocable trust naming her children that ensures that medical and other such expenses will not interfere with the transfer of the property. In the meantime, she shares all her correspondence with Delaware Highlands Conservancy with her children. What’s more, she has already begun traditions with her grandchildren that will instill the same values and reverence her father instilled in her, including planting various trees on the property and enrolling them in upcoming sessions with Women and Their Woods, which will provide an education that reinforces the sentimental connection that has taken root.

“My grandchildren tell me, ‘Your woods are better than the house!’ And the house is 200 years old and has twenty-three rooms and is pretty interesting. But they’re much more enchanted with the woods,” Kenna says. “You know, when you grow up out-of-doors, you never need toys. Whether its playing hide-and-seek, or picking up acorns, or inspecting strange toadstools, there’s a lot to absorb for kids. They’re very observant with detail. So with these excursions and seasonal rituals, allowing them to spend all this time out here at their age, I feel like I’ve succeeded in moving them along in the right direction.

STATE: Pennsylvania

SIZE OF LAND: 74 acres

FAMILY LINE: 4 siblings

TOOLS USED: No legal tools; conversations among siblings

The Park siblings—sisters Carol and Mary, brothers Jim and Steve—are approaching a kind of crossroads. As fifth-generation landowners, they have assumed two important responsibilities: managing the property and ensuring that it remains in the family for generations to come. That’s because their seventy-four acres in Columbia County, Pennsylvania, isn’t just an asset, but a site that has played a role in shaping the family’s identity.

“Since I was five years old, it’s always been mentioned that this land needs to stay in the family,” says Carol. “So there were expectations set very early in life. You know, ‘This is how the Park family does this.’ So whoever has been in possession of the property has needed to decide who was going to be the one to maintain it, who would ultimately buy the others out. In the previous generation, that was our father and mother. They bought it from my father’s siblings and very quickly turned around and sold it to us, with the expectation that we kids would figure it out. We haven’t really done that yet, we just know that it will get figured out, because that’s the expectation we’ve had for sixty years.”

The land was originally acquired in 1846 by Orrin Park, who bought 100 acres to farm just north of Bloomsburg. Eventually, Park fell into arrears on the property, and it was ultimately sold at a sheriff’s auction to clear the title. Orrin’s wife, Sarah, was able to buy a portion of the land back in 1871—approximately seventy-four acres, which has remained in the family’s possession since. The land was farmed for three generations, after which it became a family retreat. Mary, Carol, Steve, and Jim all share fond memories of visiting the land as children, in particular during Thanksgiving reunions, a cherished multi-day ritual that dates back decades for the Parks.

“The unfortunate cycle for most people is that land gets divided. If that were our case, you’d end up with seventy-four acres split four ways, and suddenly you’ve got the next generation and twenty acres get split two or three ways, and suddenly you don’t have a big enough parcel to forest anymore.”

All in their sixties, the siblings have different interests, distinct lives, and lifestyles that affect the role they play in the property’s future. And while they all share a commitment to the land’s integrity, the siblings haven’t always seen eye-to-eye on best practices, especially when it comes to the pros and cons of development. In recent years, when Citrus Petroleum began showing interest in the region’s potential gas resources, Jim Park helped write a lease agreement that represented hundreds of families—with thousands of acres in the area—and approached the company with an offer to lease exploration rights. While the Park siblings signed on, Carol and Mary did so reluctantly. “There was a definite divide in what our interests were,” Mary says.

Having been intimately involved in constructing the agreement, however, Jim was much more confident. “We were very thorough about what we wanted,” he says, citing provisions in the lease that gave him peace of mind that any fracking operation would not risk the ecological integrity of the land. “The behavior of any drilling company coming in would have been tightly controlled, and so we made an informed decision to take that risk. We have some experience in this matter, because my mother’s farm, from her family, has had a gas well on it for many years. So we had some inkling of what can happen on the downside.” In the end, the Parks leased the rights, and five years later, Citrus Petroleum moved on, giving the Parks a cash infusion and ultimately leaving the land intact.

“When you talk about resource development, it’s the most highly regulated industry on the planet—at least, in this country,” Steve says, adding that while he shares the values behind conservation, he also appreciates the independence an easement would restrict. “I’m certainly not thinking that developing the property is the right answer, but at the same time I’m defensive about the idea of giving up options, or foreclosing on options.”

Among the five members of the next generation, Steve’s and Mary’s children have expressed the most interest. Carol has no children of her own, and with retirement in mind, is prepared to divest herself of the property. Her ability to do so comes down to which sibling or combination of siblings is best positioned to buy her share—a layered question, since it comes down to a combination of wherewithal and genuine passion for the land.

“The unfortunate cycle for most people is that land gets divided,” Carol says. “If that were our case, you’d end up with seventy-four acres split four ways, and suddenly you’ve got the next generation and twenty acres get split two or three ways, and suddenly you don’t have a big enough parcel to forest anymore.”

And yet, she adds, “we’ve never felt the need to become that organized about it. It’s very loose. We’re all educated, we all have friends who are lawyers, we’ve all been counseled that we should be a little more structured and have a contract. But many of us feel that the expectation from prior generations is so ingrained in us that we just don’t feel the need right now. Could that change? Sure, but right now it appears we’re all on the same wavelength.”