Plant Propagation from Seed

ID

426-001 (SPES-682P)

EXPERT REVIEWED

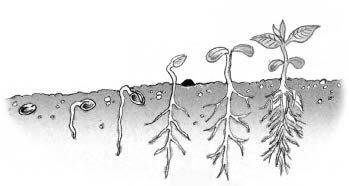

Sexual propagation involves the union of the pollen (male) with the egg (female) to produce a seed. The seed is made up of three main parts: the outer seed coat, which protects the seed; a food reserve (e.g., the endosperm); and the embryo, which is the young plant itself. When a seed is mature and put in a favorable environment, it will germinate, or begin active growth. In the following section, seed germination and transplanting of seedswill be discussed.

Flower and Vegetable Seed

To obtain quality plants, start with good quality seed from a reliable dealer. Select varieties to provide the size, color, and habit of growth desired. Choose varieties adapted to your area which will reach maturity before an early frost. Many new vegetable and flowervarieties are hybrids, which cost a little more than open pollinated types. However, hybrid plants usually have more vigor, more uniformity, and better production than nonhybrids and sometimes have specific disease resistance or other unique cultural characteristics.

Although some seeds will keep for several years if stored properly, it is advisable to purchase only enough seed for the current year’s use. Good seed will not contain seed of any other crop, weeds, or other debris. Printing on the seed packet usually indicates essential information about the variety, the year for which the seeds were packaged, germination percentage you may typically expect, and notes of any chemical seed treatment. If seeds are obtained well in advance of the actual sowing date or are stored surplus seeds, keep them in a cool, dry place. Laminated foil packets help ensure dry storage. Paper packets are best kept in tightly closed containers and maintained around 40oF in a low humidity environment.

Some gardeners save seed from their own gardens; however, if such seed are the result of random pollination by insects or other natural agents, they may not produce plants typical of the parents. This is especially true of the many hybrid varieties. Most seed companies take great care in handling seeds properly. Generally, do not expect more than 65 to 80% of the seeds to germinate. From those germinating, expect about 60 to 75% to produce satisfactory, vigorous, sturdy seedlings.

Germination

There are four environmental factors which affect germination: water, oxygen, light, and temperature.

Water

The first step in the germination process is the imbibition or absorption of water. Even though seeds have great absorbing power due to the nature of the seed coat, the amount of available water in the germination medium affects the uptake of water. An adequate, continuous supply of water is important to ensure germination. Once the germination process has begun, a dry period will cause the death of the embryo.

Light

Light is known to stimulate or to inhibit germination of some seed. The light reaction involved here is a complex process. Some crops which have a requirement for light to assist seed germination are ageratum, begonia, browallia, impatiens, lettuce, and petunia. Conversely, calendula, centaurea, annual phlox, verbena, and vinca will germinate best in the dark. Other plants are not specific at all. Seed catalogs and seed packets often list germination or cultural tips for individual varieties. When sowing light-requiring seed, do as nature does and leave them on the soil surface. If they are covered at all, cover them lightly with fine peat moss or fine vermiculite. These two materials, if not applied too heavily, will permit some light to reach the seed without limiting germination and will help keep soil uniformly moist. When starting seed in the home, supplemental light can be provided by fluorescent fixtures suspended 6 to 12 inches above the seeds for 16 hours a day.

Oxygen

Respiration takes place in all viable seed. The respiration in dormant seed is low, but some oxygen is required. The respiration rate increases during germination. Therefore, the medium in which the seeds are placed should be loose and well-aerated. If the oxygen supply during germination is limited or reduced, germination can be severely retarded or inhibited.

Temperature

A favorable temperature is another important requirement of germination. It not only affects the germination percentage but also the rate of germination. Some seeds will germinate over a wide range of temperatures, whereas others require a narrow range. Many seed have minimum, maximum, and optimum temperatures at which they germinate. For example, tomato seed has a minimum germination temperature of 50˚F and a maximum temperature of 95˚F, but an optimum germination temperature of about 80˚F. Where germination temperatures are listed, they are usually the optimum temperatures unless otherwise specified. Generally, 65 to 75˚F is best for most plants. This often means the germination flats may have to be placed in special chambers or on radiators, heating cables, or heating mats to maintain optimum temperature. The importance of maintaining proper soil and air temperature to achieve maximum germination percentages cannot be over-emphasized.

Germination will begin when certain internal requirements have been met. A seed must have a mature embryo, contain a large enough endosperm to sustain the embryo during germination, and contain sufficient hormones or auxins to initiate the process. Some seeds have a dormancy requirement also.

Methods of Breaking Seed Dormancy

One of the functions of dormancy is to prevent a seed from germinating before it is surrounded by a favorable environment. In some trees and shrubs, seed dormancy is difficult to break, even when the environment is ideal. Various treatments are performed on the seed to break dormancy and begin germination.

Seed Scarification

Seed scarification involves breaking, scratching, or softening the seed coat so that water can enter and begin the germination process. There are several methods of scarifying seeds. In acid scarification, seeds are put in a glass container and covered with concentrated sulfuric acid. The seeds are gently stirred and allowed to soak from 10 minutes to several hours, depending on the hardness of the seed coat. When the seed coat has become thin, the seeds can be removed, washed, and planted. Another scarification method is mechanical. Seeds are filed with a metal file, rubbed with sandpaper, or cracked with a hammer to weaken the seed coat. Hot water scarification involves putting the seed into hot water (170 to 212˚F). The seeds are allowed to soak in the water, as it cools, for 12 to 24 hours before being planted. A fourth method is one of warm, moist scarification. In this case, seeds are stored in nonsterile, warm, damp containers where the seed coat will be broken down by decay over several months.

Seed Stratification

Seeds of some fall-ripening trees and shrubs of the temperate zone will not germinate unless chilled underground as they overwinter. This so called “afterripening” may be accomplished artificially by a practice called stratification.

The following procedure is usually successful. Put damp sand or vermiculite in a clay pot to about 1 inch from the top. Remove the fleshy outer coating (fruit) from the seed, if present. Place the seeds on top of the medium and cover with 1/2 inch of damp sand or vermiculite. Place the pot containing the moist medium and seeds in a plastic bag and seal. Place the bag in a refrigerator. Periodically check to see that the medium is moist, but not wet. Additional water will probably not be necessary. After 10 to 12 weeks, remove the bag from the refrigerator. Take the pot out and set it in a warm place in the house. Water often enough to keep the medium moist. Soon the seedlings should emerge. When the young plants are about 3 inches tall, transplant them into pots to grow until they are ready to be set outside.

Another procedure that is usually successful uses sphagnum moss or peat moss. Wet the moss thoroughly, then squeeze out the excess water with your hands. Mix seed with the sphagnum or peat and place in a plastic bag. Seal the bag and put it in a refrigerator. Check periodically. If there is condensation on the inside of the bag, the process will probably be successful. After 10 to 12 weeks remove the bag from the refrigerator. Plant the seeds in pots to germinate and grow. Handle seeds carefully. Often the small roots and shoots are emerging at the end of the stratification period. Care must be taken not to break these off. Temperatures in the range of 35 to 45˚F are effective. Most refrigerators operate in this range. Seeds of most fruit and nut trees can be successfully germinated by these procedures. Seeds of peaches should be removed from the hard pit. Care must be taken when cracking the pits. Any injury to the seed itself can be an entry path for disease organisms.

Starting Seeds Indoors

Media

A wide range of materials can be used to start seeds, from plain vermiculite or mixtures of soilless media to the various amended soil mixes. With experience, you will learn to determine what works best under your conditions. However, keep in mind what the good qualities of a germinating medium are. It should be rather fine and uniform, yet well-aerated and loose. It should be free of insects, disease organisms, and weed seeds. It should also be of low fertility or total soluble salts and capable of holding and moving moisture by capillary action. Traditionally, one mixture which has been used to supply these factors is a combination of a sterilized soil, a sand or vermiculite or perlite, and a peat moss. Most frequently today, seedlings are started in a synthetic soil mix composed of sphagnum peat moss and vermiculite.

The importance of using a sterile medium and container cannot be over-emphasized. The home gardener can treat a small quantity of soil mixture in an oven. Place the slightly moist soil in a heat-resistant container in an oven set at about 250˚F. Use a candy or meat thermometer to ensure that the mix reaches a temperature of 180˚F for at least 1/2 hour. Avoid over-heating as this can be extremely damaging to the soil. Be aware that the heat will release very unpleasant odors in the process of sterilization. (An oven roasting bag can help reduce this.) This treatment should prevent damping-off and other plant diseases, as well as eliminate potential plant pests. Growing containers and implements should be washed to remove any debris, then rinsed in a solution of 1 part chlorine bleach to 9 parts water.

An artificial, soilless mix also provides the desired qualities of a good germination medium. The basic ingredients of such a mix are sphagnum peat moss and vermiculite, both of which are generally free of diseases, weed seeds, and insects. Sphagnum peat moss also contains anti-fungal properties which can be beneficial for seedlings. The ingredients are also readily available, easy to handle, lightweight, and produce uniform plant growth. “Peat-lite” mixes or similar products are commercially available or can be made at home using this recipe: 4 quarts of shredded sphagnum peat moss, 4 quarts of fine vermiculite, 1 tablespoon of superphosphate, and 2 tablespoons of ground limestone. Mix thoroughly. These mixes have little fertility, so seedlings must be watered with a diluted fertilizer solution soon after they emerge. Do not use garden soil by itself to start seedlings; it is not sterile, is too heavy, and will not drain well.

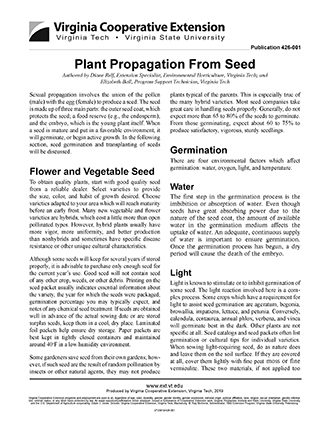

Containers

Flats and trays can be purchased or you can make your own from scrap lumber. A convenient size to handle would be about 12 to 18 inches long, 12 inches wide, and 2 inches deep. Leave cracks of about 1/2 inch between the boards in the bottom or drill a series of holes to ensure good drainage.

You can also make your own containers for starting seeds by recycling such things as cottage cheese containers, the bottoms of milk cartons or bleach containers, and pie pans, as long as good drainage is provided. At least one company has developed a form for recycling newspaper into pots, and another has developed a method for the consumer to make and use compressed blocks of soil mix instead of pots.

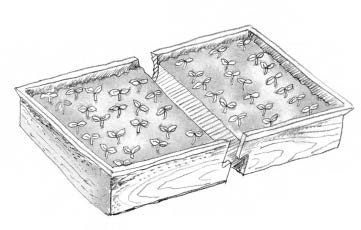

Clay or plastic pots can be used, and numerous types of pots and strips made of compressed peat are also on the market. Plant bands and plastic cell packs are also available. Each cell or minipot holds a single plant which reduces the risk of root injury when transplanting. Peat pellets, peat or fiber-based blocks, and expanded foam cubes can also be used for seeding.

Seedling

The proper time for sowing seeds for transplants depends upon when plants may safely be moved outdoors in your area. This period may range from 4 to 12 weeks prior to transplanting, depending upon the speed of germination, the rate of growth, and the cultural conditions provided. A common mistake is to sow the seeds too early and then attempt to hold the seedlings back under poor light or improper temperature ranges. This usually results in tall, weak, spindly plants which do not perform well in the garden.

After selecting a container, fill it to within 3/4 inch of the top with moistened growing medium. For very small seeds, at least the top 1/4 inch should be a fine, screened mix or a layer of vermiculite. Firm the medium at the corners and edges with your fingers or a block of wood to provide a uniform, flat surface.

For medium and large seeds, make furrows 1 to 2 inches apart and 1/8 to 1/4 inch deep across the surface of the container using a narrow board or pot label. By sowing in rows, good light and air movement results, and if damping-off fungus does appear, there is less chance of it spreading. Seedlings in rows are easier to label and handle at transplanting time than those which have been sown in a broadcast manner. Sow the seeds thinly and uniformly in the rows by gently tapping the packet of seed as it is moved along the row. Lightly cover the seed with dry vermiculite or sifted medium if they require darkness for germination. A suitable planting depth is usually about twice the diameter of the seed.

Do not plant seeds too deeply. Extremely fine seed such as petunia, begonia, and snapdragon are not covered, but lightly pressed into the medium or watered in with a fine mist. If these seeds are broadcast, strive for a uniform stand by sowing half the seeds in one direction, then sowing the other way with the remaining seed in a crossing pattern.

Large seeds are frequently sown directly into some sort of a small container or cell pack which eliminates the need for early transplanting. Usually 2 or 3 seeds are sown per unit and later thinned to allow the strongest seedling to grow.

Pregermination

Another method of starting seeds is pregermination. This method involves sprouting the seeds before they are planted in pots (or in the garden). This reduces the time to germination, as the temperature and moisture are easy to control. A high percentage of germination is achieved since environmental factors are optimum. Lay seeds between the folds of a cotton cloth or on a layer of vermiculite in a shallow pan. Keep moist, in a warm place. When roots begin to show, place the seeds in containers or plant them directly in the garden. While transplanting seedlings, be careful not to break off tender roots. Continued attention to watering is critical.

When planting seeds in a container that will be set out in the garden later, place 1 seed in a 2- to 3-inch container. Plant the seeds at only 1/2 the recommended depth. Gently press a little soil over the sprouted seed and then add about 1/4 inch of milled sphagnum or sand to the soil surface. These materials will keep the surface uniformly moist and are easy for the shoot to push through. Keep in a warm place and care for them as for any other newly transplanted seedlings.

Watering

After the seed has been sown, moisten the planting mix thoroughly. Use a fine mist or place the containers in a pan or tray which contains about 1 inch of warm water. Avoid splashing or excessive flooding which might displace small seeds. When the planting mix is saturated, set the container aside to drain. The soil should be moist but not wet.

Ideally, seed flats should remain sufficiently moist during the germination period without having to add water. One way to maintain moisture is to slip the whole flat or pot into a clear plastic bag after the initial watering. The plastic should be at least 1 inch from the soil. Many home gardeners cover their flats with panes of glass instead of using a plastic sleeve. Keep the container out of direct sunlight, otherwise the temperature may rise to the point where the seeds will be harmed. Be sure to remove the plastic bag or glass cover as soon as the first seedlings appear. Surface watering can then be practiced if care and good judgment are used.

Lack of uniformity, overwatering, or drying out are problems related to manual watering. If you have a greenhouse, excellent germination and moisture uniformity can be obtained with a low-pressure misting system. Four seconds of mist every 6 minutes or 10 seconds of mist every 15 minutes during the daytime in spring seems to be satisfactory. Bottom heat is an asset with a mist system. Subirrigation or watering from below may work well, keeping the flats moist. Capillary mats work well for this purpose. They are usually thick fibrous mats on which seedling flats are placed. The mats are irrigated with a hose, and through capillary action, water is wicked into the seed flats through the drainage holes in the flat. However, as the flats or pots must sit in water constantly, the soil may absorb too much water, and the seeds may rot due to lack of oxygen.

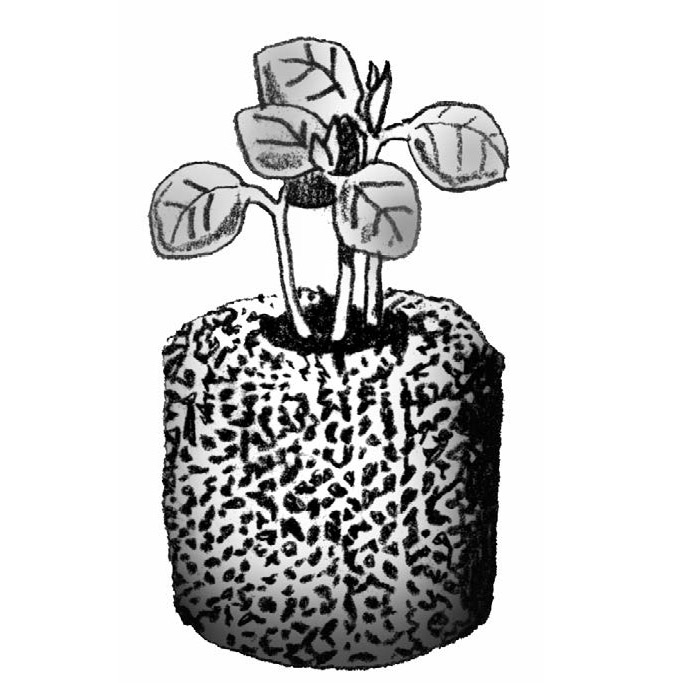

Temperature and Light

Several factors for good germination have already been mentioned. The last item, and by no means the least important, is temperature. Since most seeds will germinate best at an optimum temperature that is usually higher than most home night temperatures, often special warm areas must be provided. The use of thermostatically controlled heating cables is an excellent method of providing constant heat. After germination and seedling establishment, move the flats to a light, airy, cooler location, at a 55 to 60˚F night temperature and a 65 to 70˚F day reading. This will prevent soft, leggy growth and minimize disease troubles.

After germination and seedling establishment, move the flats to a light, airy, cooler location, at a 55 to 60˚F night temperature and a 65 to 70˚F day reading. This will prevent soft, leggy growth and minimize disease troubles. Some crops, of course, may germinate or grow best at a different constant temperature and must be handled separately from the bulk of the plants.

Seedlings must receive bright light after germination. Place them in a window facing south, if possible. If a large, bright window is not available, place the seedlings under a fluorescent light. Use two 40-watt, coolwhite fluorescent tubes or special plant growth lamps. Position the plants 6 inches from the tubes and keep the lights on about 16 hours each day. As the seedlings grow, the lights should be raised. When seedlings have formed 1 to 2 sets of true leaves they are ready to be transplanted.

Transplanting and Handling

If the plants have not been seeded in individual containers, they must be transplanted to give them proper growing space. One of the most common mistakes made is leaving the seedlings in the seed flat too long. The ideal time to transplant young seedlings is when they are small and there is less interruption of growth. This is usually when 1 or 2 first true leaves appear above or between the cotyledon leaves (the cotyledons or seed leaves are the first leaves the seedling produces). Don’t let plants get hard and stunted or tall and leggy.

Seedling growing mixes and containers can be purchased or prepared similar to those mentioned for germinating seed. The medium should contain more plant nutrients than a germination mix, however. Some commercial soilless mixes have fertilizer already added.

Containers for Transplanting

There is a wide variety of containers from which to choose for transplanting seedlings. These containers should be economical, durable, and make good use of space. The type selected will depend on the type of plant to be transplanted and individual growing conditions. Standard pots are not recommended for the transplant from germination flats as they waste a great deal of space and may not dry out rapidly enough for the seedling to have sufficient oxygen for proper development.

There are many types of containers available commercially. Those made out of pressed peat can be purchased in varying sizes. Individual pots or strips of connected pots fit closely together, are inexpensive, and can be planted directly in the garden.

When setting out plants grown in peat pots, be sure to cover the pot completely. If the top edge of the peat pot extends above the soil level, it will act as a wick, and draw water away from the soil in the pot. To avoid this, tear off the top lip of the pot and then plant flush with the soil level. Compressed peat pellets, when soaked in water, expand to form compact, individual pots. They waste no space, don’t fall apart as badly as peat pots, and can be set directly out in the garden. If you wish to avoid transplanting seedlings altogether, compressed peat pellets are excellent for direct sowing.

Community packs are containers in which there is room to plant several plants. These are generally inexpensive. The main disadvantage of a community pack is that the roots of the individual plants must be broken or cut apart when separating them to put out in the garden. Cell packs, which are strips of connected individual pots, are also available in plastic and are frequently used by commercial bedding plant growers, as they withstand frequent handling. In addition, many homeowners find a variety of materials from around the house useful for containers. These homemade containers should be deep enough to provide adequate soil and have plenty of drainage holes in the bottom. For example, styrofoam egg cartons make good cell packs.

Transplanting

Carefully dig up a group of the small plants with a knife or plant label. Avoid tearing roots in the process. Let the group of seedlings fall apart and pick out individual plants. Gently ease them apart in small groups which will make it easier to separate individual plants. Handle small seedlings by their leaves, not their delicate stems. Punch a hole in the medium into which the seedling will be planted. Make it deep enough so the seedling can be put at the same depth it was growing in the seed flat. After planting, firm the soil and water gently. Keep newly transplanted seedlings in the shade for a few days, or place them under fluorescent lights. Keep them away from direct heat sources. Begin a fertilization program. When fertilizing, use a soluble house plant fertilizer, at the dilution recommended by the manufacturer, about every 2 weeks after the seedlings are established. Remember that young seedlings are easily damaged by too much fertilizer, especially if they are under any moisture stress.

Hardening Plants

Hardening is the process of altering the quality of plant growth to withstand the change in environmental conditions which occurs when plants are transferred from a greenhouse or home to the garden. A severe check in growth may occur if plants produced in the home are planted outdoors without a transition period. Hardening is most critical with early crops, when adverse climatic conditions can be expected.

Hardening can be accomplished by gradually lowering temperatures and relative humidity and reducing water. This procedure results in an accumulation of carbohydrates and a thickening of cell walls. A change from a soft, succulent type of growth to a firmer, harder type is desired.

This process should be started at least 2 weeks before planting in the garden. If possible, plants should be moved to a 45 to 50˚F temperature indoor or outdoor shady location. A coldframe is excellent for this purpose. When put outdoors, plants should be shaded, then gradually moved into sunlight. Each day, gradually increase the length of exposure. Don’t put tender seedlings outdoors on windy days or when temperatures are below 45˚F. Reduce the frequency of watering to slow growth, but don’t allow plants to wilt. Even cold-hardy plants will be hurt if exposed to freezing temperatures before they are hardened. After proper hardening, however, they can be planted outdoors and light frosts will not damage them.

The hardening process is intended to slow plant growth. If carried to the extreme of actually stopping plant growth, significant damage can be done to certain crops. For example, cauliflower will make thumb size heads and fail to develop further if hardened too severely. Cucumbers and melons will stop growth if hardened.

Original publication reviewed by Joyce Latimer, Extension Specialist, Horticulture, Virginia Tech; Roger Harris, Virginia Tech Department of Horticulture; Alan McDaniel, Virginia Tech Department of Horticulutre; and John Arbogast, Extension Agent, Environmental Horticulture, Roanoke, Virginia

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

October 11, 2019