Fall Armyworm in Vegetable Crops

ID

444-015 (ENTO-599NP)

Introduction

Fall armyworm (FAW), Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith), is in the family Noctuidae of the order Lepidoptera. It is native to the tropical regions of the Western Hemisphere from the United States to Argentina. Fall armyworm is different from most other insects in the temperate region in that it has no diapause mechanism (Luginbill 1928, Sparks 1979). In the US, this species overwinters in the Gulf Coast states and continuously migrates north during the spring and summer months as temperatures become suitable in the northern latitudes (Luginbill 1928, Sparks 1979).

Distribution

Adult FAW are strong fliers and can disperse long distances annually during the summer months. They have been recorded in all US states east of the Rocky Mountains (EPPO 2024); however, its range as a regular and severe pest of vegetable crops in the US primarily concerns the southeastern states. Since 2016, FAW has also been reported as present and causing significant crop injury in Africa, the Middle East, India, China, southeast Asia, and Oceania (EPPO 2024). The dispersal capability of FAW largely depends on the weather conditions in its overwintering region and subsequent weather patterns that might assist the migration of populations (Sparks 1979).

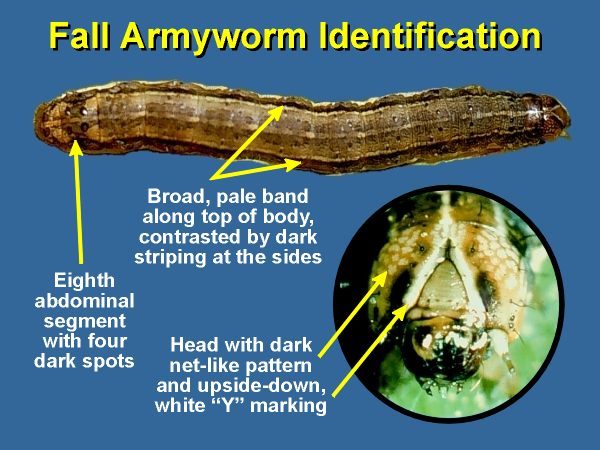

Identification

Larvae are hairless with smooth skin, and vary in color from light tan or green to dark brown (nearly black) (Fig. 1). Three yellowish-white lines traverse the sides and back from head to tail and four dark circular spots are evident on the upper portion of each abdominal segment. The front of the head is marked with a prominent inverted white Y (Fig. 1), but this characteristic is not always a reliable identifier.

.Larvae vary in length from 1/2 in (2mm) as first instar larvae to 3/4 - 1 in (35 - 50mm) as mature larvae. The forewing of adult male moths is generally shaded gray and brown, with triangular white spots at the tip and near the center of the wing (Fig. 2). The forewings of females range from a uniform grayish brown to a fine mottling of gray and brown. The hind wing is iridescent silver-white with a narrow dark border in both sexes (Fig. 2).

Life Cycle

Seasonal FAW activities in Virginia begin with egg laying by moths migrating northward from their ranges in the southern United States and Mexico. The moths persistently migrate and lay eggs throughout the summer. Female FAW moths can produce approximately 1,000 eggs over her life span, and deposit them in clusters containing up to four hundred eggs each (Fig. 3). New generations can occur approximately every 30 days depending on conditions (Barfield et al. 1978; Ashok et al. 2021). Neonates produce a silken thread, which allows them to drop or be blown (aka ballooning) to other areas. In Virginia, FAW are most active in the late summer/fall (See Fig. 4), beginning in early July.

Caterpillars can cause severe damage and will eventually move into adjoining fields. They feed more during daylight hours than other armyworms and large populations can rapidly lead to severe damage.

Figure 4. Typical fall armyworm moth flights in Virginia showing the late summer/fall populations.

Host Plants

Fall armyworms feed on a wider range of plants than do true armyworms, Pseudaletia unipuncta (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). The FAW is a major pest of sweet corn, tomatoes, and peppers in Virginia and other southeastern states (Luginbill 1928; EPPO 2024).

Although FAW has a wide host range with over eighty plants reported, it clearly prefers grasses (Chang et al. 1987). The field crops frequently injured include alfalfa, barley, Bermudagrass, buckwheat, cotton, clover, corn, oats, millet, peanuts, rice, ryegrass, sorghum, sugarbeets, sudangrass, soybeans, sugarcane, timothy, tobacco, and wheat (Luginbill 1928; Chang et. al 1987; EPPO 2024). Among vegetable crops, only sweet corn is regularly damaged. Other vegetable crops attacked include crucifer crops. Weeds known to serve as hosts include bentgrass, Agrostis spp.; crabgrass, Digitaria spp.; Johnsongrass, Sorghum halepense; morning glory, Ipomoea spp.; nutsedge, Cyperus spp.; pigweed, Amaranthus spp.; and sandspur, Cenchrus tribuloides (EPPO 2024). There is evidence that FAW strains exist based primarily on their host plant preference. The corn strain feeds principally on corn, but also on sorghum, cotton, and others if they are found growing nearby primary host plants. The rice strain feeds principally on rice, Bermudagrass, and Johnsongrass (Pashley et al. 1995).

Armyworm Injury to Crops

Fall armyworm larvae primarily cause damage by consuming foliage. In pepper and tomato, FAW can cause severe damage to the fruit, resulting in premature drop and fruit rot. The young larvae first feed near the ground where the damage goes unnoticed. They initially consume leaf tissue from one side, leaving the opposite epidermal layer intact. By the second or third instar, larvae begin to make holes in leaves, and eat from the edge of the leaves inward. Larval densities are usually reduced to one to two per plant due to cannibalistic behavior (Luginbill 1928). Older larvae cause extensive defoliation, often leaving the plant with a ragged, torn appearance. In corn, they sometimes bore through the husk and feed on the kernels (Fig. 5). Outbreaks typically happen in the fall and are worse with frequent rains and cooler temperatures (Sparks 1979). When larvae are abundant, they can defoliate entire plants. The larvae disperse in large numbers, consuming nearly all vegetation in their path, thus the name "armyworm”.

Managing Fall Armyworm in Vegetable Crops

Sampling

Moth populations can be sampled with black-light and pheromone traps (Mitchell 1979). Pheromone traps are more efficient and sensitive to regional changes.

Pheromone traps will only trap male moths and should be suspended at canopy height in the crop (Sekul and Sparks 1976). Catches are not necessarily good indicators of density but indicate the presence of moths in an area. Pheromone trap catches of 10 to 20 per night (70 to 100 per week) signal the need to begin insecticide applications to protect fruit. Once moths are detected, it is advisable to scout for eggs and larvae. Scouting 20 plants in five locations or ten plants in ten locations is generally considered to be adequate to assess the proportion of plants infested. Sampling to determine larval density often requires large sample sizes (≥ 30), especially when larval densities are low or larvae are young.

Biological Control

Numerous species of parasitoids and predators affect FAW (Abbas et al. 2022). The most frequent wasp parasitoids reared from larvae in the United States are Cotesia marginiventris (Cresson) and Chelonus texanus (Cresson) (both Hymenoptera: Braconidae) species that are also associated with other noctuid species (Meagher et al. 2016). Among fly parasitoids, usually the most common species is Archytas marmoratus (Townsend) (Diptera: Tachinidae). However, the dominant parasitoid in each area varies annually and by location.

Chemical Control

Insecticides are frequently used to protect crops against FAW damage. Some crops, like sweet corn, require as many as four applications per week during the silking and ear stages. Some resistance to insecticides has been noted, with resistance levels varying regionally (Yu 1991, Yu et al. 2003, Yainna et al. 2023). Treatments using insecticides should be made when insect populations and/or damage levels reach economic thresholds (Overton et al. 2021). For control recommendations on vegetables, refer to the most recent Mid-Atlantic Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations VCE Publ. No. 456-420 (SPES- 586P) https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/456/456-420/456- 420.html.

References

Abbas, A., Ullah, F., Hafeez, M., Han, X., Dara, M.Z.N., Gul, H. and Zhao, C.R., 2022. Biological control of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Agronomy, 12(11), p.2704.

Ashok, K., Balasubramani, V., Kennedy, J.S., Geethalakshmi, V., Jeyakumar, P. and Sathiah, N., 2021. Effect of elevated temperature on the population dynamics of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Journal of Environmental Biology, 42, pp.1098-1105.

Barfield, C.S., Mitchell, E.R. and Poeb, S.L., 1978. A temperature-dependent model for fall armyworm development. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 71(1), pp.70-74.

Chang, N.T., Lynch, R.E., Slansky, F.A., Wiseman, B.R. and Habeck, D.H., 1987. Quantitative utilization of selected grasses by fall armyworm larvae. Entomologia experimentalis et applicata, 45(1), pp.29-35.

EPPO. 2024. Spodoptera frugiperda. EPPO datasheets on pests recommended for regulation. https://gd.eppo.int (accessed 2024-09-03).

Luginbill, P., 1928. The fall army worm. US Department of Agriculture. Technical Bulletin No. 34.

Meagher Jr, R.L., Nuessly, G.S., Nagoshi, R.N. and Hay-Roe, M.M., 2016. Parasitoids attacking fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in sweet corn habitats. Biological Control, 95, pp.66-72.

Mitchell, E.R., 1979. Monitoring adult populations of the fall armyworm. Florida Entomologist, pp.91-98.

Overton, K., Maino, J.L., Day, R., Umina, P.A., Bett, B., Carnovale, D., Ekesi, S., Meagher, R. and Reynolds, O.L., 2021. Global crop impacts, yield losses and action thresholds for fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda): A review. Crop Protection, 145, p.105641.

Pashley, D.P., Hardy, T.N. and Hammond, A.M., 1995. Host effects on developmental and reproductive traits in fall armyworm strains (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 88(6), pp.748-755.

Sekul, A.A., and A.N. Sparks. 1976. Sex attractant of the fall armyworm moth. USDA Technical Bulletin 1542. 6 pp.

Sparks, A.N., 1979. A review of the biology of the fall armyworm. Florida entomologist, pp.82-87.

Yainna, S., Nègre, N., Silvie, P.J., Brévault, T., Tay, W.T., Gordon, K., Dalençon, E., Walsh, T. and Nam, K., 2021. Geographic monitoring of insecticide resistance mutations in native and invasive populations of the fall armyworm. Insects, 12(5), p.468.

Yu, S.J., 1991. Insecticide resistance in the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith). Pesticide biochemistry and physiology, 39(1), pp.84- 91.

Yu, S.J., Nguyen, S.N. and Abo-Elghar, G.E., 2003. Biochemical characteristics of insecticide resistance in the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith). Pesticide biochemistry and physiology, 77(1), pp.1-11.

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

October 14, 2024