Colorado Potato Beetle

ID

444-012 (ENTO-582NP)

EXPERT REVIEWED

Introduction

The Colorado potato beetle (CPB), Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), is native to North America and was first described in 1824. It feeds on plants in the family Solanaceae including potato, pepper, tomato, tomatillo, eggplant, weeds such as the nightshades, and its native host buffalo bur. A preference for potato was discovered in Nebraska as the cultivated range overlapped with the native range of buffalo bur in the mid-1800’s.

Eastward expansion of populations quickly ensued and CPB reached the east coast by 1874. Today, CPB is considered a major pest of potato in the Northeast US.

A similar beetle can commonly be confused with CPB and is called the false potato beetle, Leptinotarsa juncta. These are found in the mid- Atlantic and southeast US. False potato beetles feed almost exclusively on eggplant and are not considered a major pest in lesser numbers.

As a pest of solanaceous plants, CPB has a special ability to rapidly develop insecticide resistance through gene regulation. Across various regional populations CPB has developed widespread insecticide resistance to all major chemical classes. Management of CPB relies on effective rotations of chemical modes of action, and cultural and biological control.

Identification

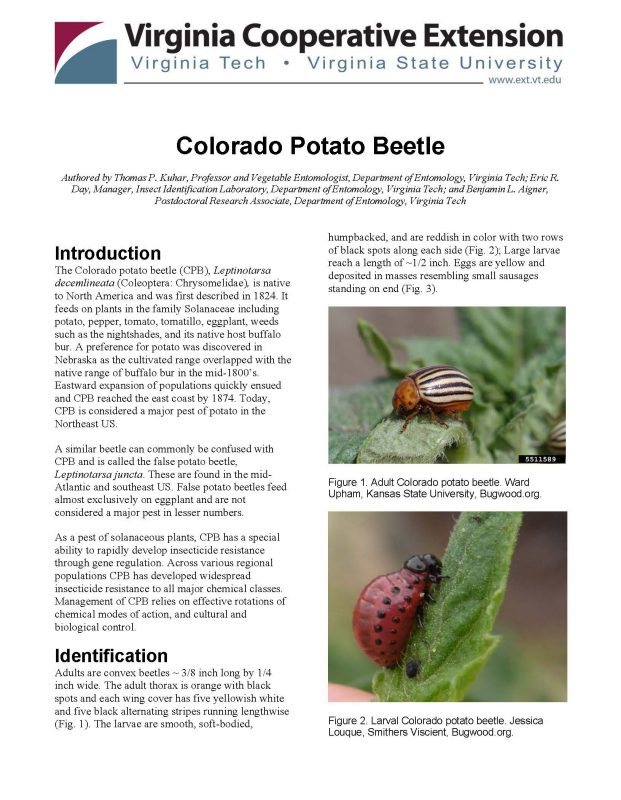

Adults are convex beetles ~ 3/8 inch long by 1/4 inch wide. The adult thorax is orange with black spots and each wing cover has five yellowish white and five black alternating stripes running lengthwise (Fig. 1). The larvae are smooth, soft-bodied, humpbacked, and are reddish in color with two rows of black spots along each side (Fig. 2); Large larvae reach a length of ~1/2 inch. Eggs are yellow and deposited in masses resembling small sausages standing on end (Fig. 3).

Distribution & Host Range

The Colorado potato beetle (CPB) is found in most regions of the United States except for the Pacific Coast. It feeds exclusively on the foliage of cultivated and wild plants in the nightshade family (Solanaceae). It is a major pest of potatoes and eggplant, and a minor pest of tomatoes.

Life Cycle

The CPB overwinters in the soil as an adult. In the spring, the emerging beetles seek suitable host plants (such as potato) by walking, but are capable of flying long distances when temperatures exceed 80°F. A female beetle may lay several hundred eggs in her lifetime. Oviposition usually begins by early May, and the eggs are laid in tight clusters of 30 to 60, usually on the underside of host leaves (Fig. 3). The eggs hatch within four to nine days. Larvae are usually found feeding in groups on the undersides of the leaves as they pass through four instars or molts.

Larvae complete their growth in two to three weeks, and peak larval populations develop by mid- to late May when the mature larvae pupate underground in earthen cells. The pupal stage lasts from five to ten days before the summer, or first-generation, adults emerge in June.

The rate of development for each stage depends on the temperature. In eastern Virginia, potatoes are harvested in late June and July; and therefore, most of these first-generation adults will feed on the remaining potato foliage and then enter the soil to overwinter. Some of these adults, however, will produce a partial second generation on tomato, eggplant, fall potato, or other available, suitable foliage. In other states in which potatoes are grown continuously all summer, there is a substantial second generation. There is much overlap within a generation, and typically eggs, larvae, and adults can be found on host foliage at any given time within the season, although generally one stage predominates at a given time.

Description of Damage

Adults and larvae feed on foliage in the same manner (Fig. 4). If CPB adults are present early in the season, they will clip small tomato or eggplant transplants or the emerging potato shoots at the ground level. As the larvae grow, they disperse through the plant canopy and consume large portions of the foliage. Large (third and fourth instar) larvae and first-generation adults are the stages that do the most damage. If population pressure is heavy, the larvae and adults will completely defoliate the host plant and then feed on the stems. Loss of foliage weakens the plant and consequently results in reduction of marketable yield (tubers, fruit).

Organic/Biological Control

The spined soldier bug, Podisus maculiventris (Fig. 5), and the two-spotted stinkbug, Perillus bioculatus (Fig. 6), prey upon CPB eggs and larvae. Some beetles, specifically the ladybird beetle, Coleomegilla maculata (Fig. 7), and carabid beetles in the genus Lebia also prey on the eggs. Soilborne fungal pathogens such as Beauveria bassiana may cause high mortality of pupae and overwintering adults. None of these organisms, however, are capable of making an economic impact on large populations.

Cultural Control

Because CPB feeds exclusively on solanaceous crops and disperses by walking when temperatures are cool, rotation to a non-solanaceous crop is one of the most effective cultural control measures a producer can take. This is especially true in eastern Virginia, where the beetles often overwinter in the same fields in which they developed. Plastic-lined trenches along the side of a potato field where overwintering adults will enter are effective early in the season. Trenches should be at least 12 inches deep, with the sides having a slope of at least 46 degrees. A feasible option for small potato fields is spreading a thick layer of straw mulch after planting to create a favorable environment for the potatoes and an effective barrier to adult beetles. Mechanical control methods such as flaming and handpicking beetles have also been developed.

Chemical Control & Resistance Management

CPB has developed resistance to numerous insecticides and chemical control can be difficult for some populations if the wrong products are used.

Most commercial growers use at planting (or seed- piece) applications of neonicotinoids such as imidacloprid or thiamethoxam, which move systemically from roots to above-ground plant parts to provide control of beetles for several weeks.

Several other products are available for use as foliar sprays. A complete list of insecticide options can be found in the Commercial Vegetable Production Recommendations (Virginia Coop. Ext. Pub. No.456-420). Options for organic growers include: Entrust (Spinosad) azadirachtins, and products containing Bt tenebrionis.

References

Alyokhin, A., 2009. Colorado potato beetle management on potatoes: current challenges and future prospects. Fruit, vegetable and cereal science and biotechnology, 3(1): 10-19.

Alyokhin, A., Baker, M., Mota-Sanchez, D., Dively,

G. and Grafius, E., 2008. Colorado potato beetle resistance to insecticides. American Journal of Potato Research, 85: 395-413.

Boiteau, G. and Le Blanc, J.P.R., 1992. Colorado potato beetle life stages. Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Boiteau, G. and Vernon, R.S., 2001. Physical barriers for the control of insect pests. In Physical control methods in plant protection (pp. 224- 247). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Gabryś, B. and Kordan, B., 2022. Cultural control and other non-chemical methods. In Insect Pests of Potato (pp. 297-314). Academic Press.

Hare, J.D., 1990. Ecology and management of the Colorado potato beetle. Annual review of entomology, 35(1): 81-100.

Visit Virginia Cooperative Extension: ext.vt.edu

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

February 23, 2024

The Colorado potato beetle is considered a severe pest of potato Virginia and can also be a significant pest of tomato, tomatillo, pepper, and eggplant throughout the Northeast US. Here you will find descriptions of distinguishing characteristics of eggs, larvae, and adults and how to manage them with a combination of cultural, biological, and chemical management tactics.